This week, I am sharing something different from the usual, as I don't have a habit of posting book reviews. But I thought this one deserved a long-form comment rather than a quick note elsewhere. I hope you like it!

Sometimes, a book catches you off guard and keeps coming back to you, and you want to make sure that you get it. If that’s a 5-star book, then Lies and Sorcery by Elsa Morante would probably be a 6-star to me. I have become so enthralled by it that I have spent several days since finishing it just reading about it—including some articles and chapters that added new layers to my understanding of it but also made me want to read every single book by Morante and her female contemporaries. You could even say I am starstruck.

As the fourth-cover blurb describes, Lies and Sorcery “is set in Sicily and told by Elisa, orphaned young and raised by a ‘fallen woman.’ For years, Elisa has lived in an imaginary world of her own; now, however, her guardian has died, and the young woman feels that she must abandon her fantasy life to confront the truth of her family’s tortured and dramatic history.” Interestingly, while Elisa is the narrator of this novel, her own life is not its main focus. Inspired or haunted by the ghosts of her family members, she sits in her little isolated room and writes about her maternal grandparents (the adequately pretty governess Cesira and the impoverished aristocrat Teodoro), but especially about her parents (the haughty Anna and the forever-dreamer Francisco) and the mysterious, aristocratic, and unattainable Cousin Edoardo. Indeed, the bulk of the novel is dedicated to this latter trio: to Anna’s infatuation and obsession with Edoardo (based on half-truths), Edoardo and Francisco’s friendship (based on inventions), and Francisco’s futile attempts to capture Anna’s attention and love (based on lies). It takes place in an unnamed town, during an indeterminate period, about which we are given only some information throughout the pages: there is a neighborhood of mansions inhabited by the aristocratic elite and at least two neighborhoods of multi-family buildings populated by (poor) workers; there is a school run by nuns, a university, a central market, postal service, and several churches; there are newspapers and trains and also horse-pulled chariots; there is candlelight and gas lamps and electricity; women can do some types of work outside the house and there are no mentions of war.

The book opens with an “Introduction to the Story of My Family,” which explains where Elisa currently finds herself (the empty apartment of her surrogate mother, now deceased) and why she has decided to undertake this monstrous task of dragging family skeletons from the closet (previously accompanied by phantasmagoric companions of her own making, it is now her memory and that of her bloodline that fills the empty apartment). While Elisa uses the first three chapters of her book to explain her current circumstances, she sets up what follows almost as a detective novel: instead of a whodunit, however, we have a “how did we get here?” through line. But these chapters also function as a true argumentative introduction, in the sense that they present the reader with the shape of the text that will come and announce the main topic that will be discussed in the pages that follow: the power of family myths and fables, and how a “wretched middle-class family” (24) created its own grandiose interior life at the expense of everything else (including each other).

Indeed, every single character seems to be stuck in Belle’s refrain of wanting “more than this provincial life.” But instead of acting on it, each creates their own mental version of this bigger, better, and brighter life and sticks to it, to the detriment of their possible social and emotional development. And this afflicts both those critically unprivileged and the representatives of the progressively disempowered aristocratic elite: it is a world that is crumbling, with no project of reconstruction in sight. Or, as Janet Flanner (under her pen name Genet), wrote of the book in a “Letter from Rome” in 1950: “The characters are like the rooms of an empty provincial mansion, each chamber, as it is explored, found still to contain its once elegant traditional furnishings, grown shabby through the wear and tear of life.” (102)

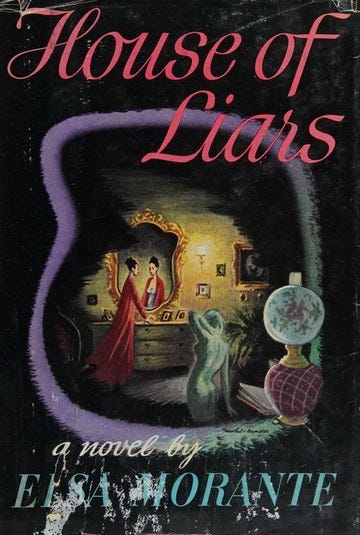

Lies and the people who tell them are, in fact, such a central part of the novel, that in 1951, when American readers were offered a translation by Adrienne Foulke edited by Andrew Chiappe, it was entitled House of Liars. Unfortunately, it went above and beyond the usual dictum of translators betraying the originals by cutting out something between 140 and 200 pages of Morante’s text (and making Morante understandably livid). Marco Bardini retraced the interventions and noted that they ranged from single words when paired with synonyms and full sentences of meta-narrative intervention, to most of religious-devotional language and imagery (and we are talking about southern Italy and its very Catholic culture), to an entire chapter (the aforementioned chapter on writing). “The evident aim,” he notes, “[was] to simplify (also taking account of the target language) a style perceived as baroque, excessive, overflowing, and awash with superfluity.” (115)

Bandini’s remark calls to the foreground the inescapable distance that separates English’s straightforwardness from latinate languages’ potential to multiply imbrication and subordination of clauses. Perhaps now in the 2020s, the anglophone audience for literary translations is a little more open to the necessary differences that languages impose on the stories they tell. But, as we can perhaps also all agree, sometimes a little something extra, especially in a story of matchless temperaments and suffering, is needed. Jenny McPhee’s translation embraces this, letting Morante’s long, winding, sometimes vertiginous sentences stand for what they are, holding the hand of the reader as it speeds through tight curves and narrow paths.

And tight curves and narrow paths are promised from the start. Elisa, as a reporter (she calls herself a “secretary”) and an interested party, almost as an academic writer, offers her reader very early on the key to the more than seven hundred pages that follow, a statement that buttresses her entire project: “Lying’s poisonous evil slithers among the branches of my family tree, on both the paternal and the maternal sides, and you shall see various aspects of this evil, both apparent and hidden, in the characters who will appear in my story.” But to this almost defeatist argumentative thesis, that could scare away readers from a tale of falsehoods (never mind the title), she quickly adds: “But you musn’t hold this against me or my story, as the whole point here is to gather reliable proof of my family’s long-inbred insanity.” (15) What follows, then, is not a pure portrait of moral degeneracy; it is an exploration into how Elisa’s specific brand of “insanity” comes to be and, through their consequences, to retrace the various elements that added to it.

If Elisa’s “Introduction” helps us read the story that follows it, it is the theme of invented narratives that is key to understanding the novel in its broader cultural setting. Originally published in 1948 but written during the German occupation of Italy while Morante herself was in hiding, Lies and Sorcery, set in an ever-so-slightly recognizable belle époque, never directly confronts fascism. Its shadow and weight are nevertheless always present. In her own introduction, McPhee states that Elisa creates a meta-narrative with the goal “to show us that whoever has control of the story, has control over us, both in fiction and in reality.” (ix) And she adds, commenting on a pivotal chapter about a specific character’s writing performance, that it shows “how language, writing, and storytelling have the power to create our reality, for better or for worse.” (xii)

But Morante, through Elisa, is equally direct:

“Those who succumb to make-believe are like madmen who go to the theater and are terrified by the tragedy they see onstage. They scream when they see the leading lady tormented and want to rush on stage to kill the tyrant causing her distress. But at least the poor madman has the excuse of not being aware of the fiction that is theater, and he certainly had nothing to do with staging the lie. But others, like my parents, fully believe the disguises they don are genuine, and they worship them, thereby rejecting their own lives on earth and, indeed, in heaven, since the only way to get there is to take part in real life.” (15)

The problem is neither storytelling nor storytelling consumption. The problem is letting aggrandizing stories provide a larger-than-life structure that disconnects the listener from the ground she stands and the people around her.

This is a book about the stories unhappy people tell themselves and others, not so much to make themselves happier, but often to make others just as miserable. All characters of consequence are storytellers, either before an audience or to themselves, all trying to make sense of their social and emotional stagnation (the two go hand-in-hand) by imposing make-believe realities onto others. And it is a book of unlikeable, quite irredeemable characters. Most come across as mean, or uncaring, or pitiful, or pathetic (and often a mix of all of the above). There’s grime on the streets, on bodies, and in hearts. Affection is never freely given, only offered as an obsession—another form of narrativizing events and feelings to give them a bigger, or at least a different, meaning. Parents and children are either put on a pedestal to be adored, despite all their obvious flaws, or thrown in the gutter to be despised. Rosaria, the surrogate mother and “fallen woman” (Elisa is never quite clear on how fallen she is), is perhaps the one warm ray of hope in the otherwise gray and cruel emotional landscape of the novel: freely loving, freely taking, and freely giving, inattentive as hard as she tries to most of the stories told around her, Rosaria seems content with the “real life” she gets to live, with her little trinkets and her little loves.

All other characters, as hard as they try, fail to make the most of their lives because they fail to understand that their lies, rather than sugarcoat the world around them, create unsurmountable barriers that fail to protect them from said world while also obfuscating any possible way out of any given pain. In the simple words of Anna, “He loved me, he alone loved me, and I rejected him in order to love a ghost. And now I don’t have anyone anymore.” (752) And it is true that Elisa sees herself as taking part in the same family tradition—shut in her bedroom populated by the voices of ghosts, her emotional growth stunted for fifteen years by her own confession. But Morante was interested in Freudian psychoanalysis, and Elisa’s act of writing—one could say then of self-writing—is tentatively framed as restorative and therapeutic, as she hopes “Who knows, perhaps with [the ghosts’s] help I may at last be able to leave this room.” (24) Or, as Sharon Wood says, “Oneiric memory transforms the menzogne [lies] of her family members—almost all now dead—into the sortilegio [sorcery] of literary writing, which alone can throw light on the ambiguities that govern our destiny.” (105)

With a fable-like tone lacking precise time and space coordinates for its action and a looming moral lesson about the dangers of telling lies, this is not a cheerful take on the power of words. But its ending points to the hope that conscientious writing could reconnect the reader to the world and its (hi)stories. The most tender moment of Elisa comes at the very end of the book, in the final pages of the “Epilogue.” It is with verses to the elusive Alvaro (first mentioned on page 11), “the most important and endearing character of all” (774), that Elisa closes the door to her haunted mansion. A mansion I would like to revisit someday. Because of its shabby furnishings.

Texts cited:

Marco Bardini, “House of Liars: The American Translation of Menzogna e sortilegio,” in Under Arturo’s Star: The Cultural Legacies of Elsa Morante, ed. Stefania Lucamante and Sharon Wood (Purdue University Press, 2006), 112-28.

Genet [Janet Flanner], “Letter from Rome,” The New Yorker, 6 Mary 1950, 102-6.

Jenny McPhee, “Introduction,” in Elsa Morante, Lies and Sorcery (trans. Jenny McPhee) (New York Review Books, 2023), vii-xiv).

Sharon Wood, “Models of Narrative in Menzogna e sortilegio,” in Under Arturo’s Star: The Cultural Legacies of Elsa Morante, ed. Stefania Lucamante and Sharon Wood (Purdue University Press, 2006), 94-111.

Other reviews:

Debora Eisenberg, “Virtuosos of self-deception,” New York Review of Books, 2 November 2023.

Vivian Gornick, “Ferrante before Ferrante,” The New York Times, 1 October 2023.

Tim Parks, “The scars of love. Elsa Morante’s urgent, exhilaritng novel of falsehood and secrecy,” TLS, 13 October 2023.

Bailey Trela, “A classic Italian novel finally gets the translation it deserves,” The Washington Post, 10 October 2023.

To watch:

Antifascism and Italian Women Writers: A conversation between translators Jenny McPhee and Ann Goldstein and historian Franco Baldasso about Alba de Céspedes, Elsa Morante, and Natalia Ginzburg (Rizzoli Bookstore, 1 February 2024).

So wonderfully said! I hope you do write more reviews like this, because now I have to get my hands on this book and soak it up. There's always something infectious about someone's passionate love for a work of literature. Excellent job, Juliana!

Listen, I'm not even done reading this post and I already know I need this book STAT.