Despite growing up in a tropical city, I do not enjoy the hot summer weather. The heat and the lethargy it facilitates, the desire to be indoors to stay somewhere with good AC or at least some shade and a working fan, the humidity—all of these contribute to my dislike for hot days.

But, as a graduate student, I learned to enjoy the summer.

Especially after starting my PhD, summer was a time that I could dedicate entirely to my interests and to my schedule. I could go to the library and spend several hours in the comfort of such a powerful AC system I had to bring a cardigan with me, sipping iced tea and only mildly aware of the world outside.

Summer was the time for relaxing, for resetting, and for researching.

It is now a time of the year that breeds nostalgia in its own way. It’s not as aesthetically pleasing as the fall, and I still dislike the rising temperatures, just as before. But I’ve come to appreciate how it sparks memories of my time deep in the thick of archival research, even if it brings about a string of events that do not necessarily take place all during the summer.

In my first summer after moving to New York, I took Intensive German for a little over a month and then high-tailed to Paris for research in July. I got my reader card for the national archives, climbed to the room where the microfilm rolls and machines were set, and settled in to finally start reading the medieval documentation I had longed to see for so many months.

And I couldn’t make a single word out of it.

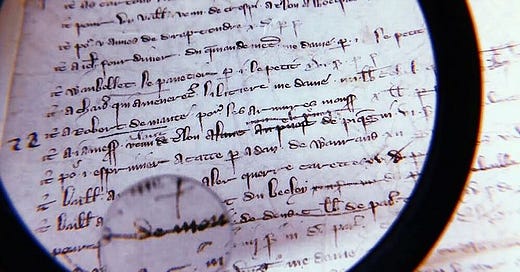

The Instagram post I shared on that day mentions none of this, of course. It is a cropped and slightly out-of-focus view of the microfilm projection, with a caption that reads “Is it too late to change my mind about being a medievalist?” As you may conclude, I didn’t change my mind (at the time), but I did have to change my plans for that summer. I decided I couldn’t spend a whole lot of time and effort in that room, not while I was in a city that I loved and not in a room that made me want to call it quits. I pivoted to preparatory research, I consulted printed catalogs and compiled information from them in sprawling documents that became so large my computer had trouble loading. I told myself I would eventually figure out how to move forward with my research, even if I couldn’t read a word of what was in those reproduced documents, all the while wondering if I could even hope to deal with reading originals or justifying seeing them in the future?

I remember this entire setting perfectly well, but I opened the aforementioned Instagram post to make sure I had correctly memorized the caption. And I was greeted with probably one of the neatest types of writing I came across in all my research years, a very clear French document hand from the fourteenth century. I did not add the shelfmark of that document so I could confirm its identity, but I came to spend so much time with its variants that the neat style became unmistakable to my eyes. And yet, in those days in the summer of 2016, I actually told someone “I much prefer a well-executed Gothic hand in Latin than these scribbles in French.” In part because yes, I loved all things extremely Gothic, but in part because of a quiet truth that I held in my heart and felt acutely in those days: it felt more like a pain not to be able to read something in French, a language I knew very well, than not to be able to read something in Latin, which I couldn’t for the life in me make sense in manuscripts at that point.

My first experience as a researcher was as an undergraduate intern. I worked in two research projects, under two different lead investigators, neither of them in medieval history. During those long months, I became acquainted with late nineteenth- and early twenty-century periodicals from Rio de Janeiro, their physical quality, and their microfilm reproductions in the Biblioteca nacional.

Microfilm is a type of microform, a shrunk-down reproduction of flat documents and pages onto film, which can then be projected much like a roll of dynamic film. Most archival material has been microfilmed in some form of monochrome (most commonly black-and-white), but copies in color also exist. One huge advantage of this support is storage, with some drawers being enough to hold what several linear feet of archival boxes. It is also a proportionately cheap way of helping the preservation of fragile materials, diminishing the exposure of these items to specific needs.

The problem is that, as a researcher, it sucks to read them for a long time. Especially, as it happened more than once during my internships, when the support for the roll was not functioning properly and you had to hold the microfilm with one hand while adjusting the zoom and focus, and taking notes, with the other. One of two occupational injuries I have truly suffered throughout the years was a back nerve pinched as I tried to catch a roll that risked following off the machine just as I sat down to take notes (the second one was when I accidentally placed a choir book onto my pinky, rather than on top of the table proper).

But even when the machines work perfectly, it can still be a pain. Because the reproduction is scaled down to fit the support, sometimes large documents need to be split into multiple frames, and even so it can be hard to properly zoom into them while retaining some legibility. The archives in Paris had magnifying glasses at hand for those cases, and throughout my time there—I did eventually go back, as you will see—I had to make use of them repeatedly. Moreover, in long series of reproductions, it is not uncommon for documents to have wildly varying values of contrast that are not properly corrected, meaning you may get the perfect balance in one photogram and then not be able to read anything in the next because that one needed more or less exposure for better readability. And if the machine lets you fast-forward to any point in the roll with ease, the repetition of barely legible lines and letters blurring before your eyes several times throughout the day can lead to some pretty annoying eye strain and headaches.

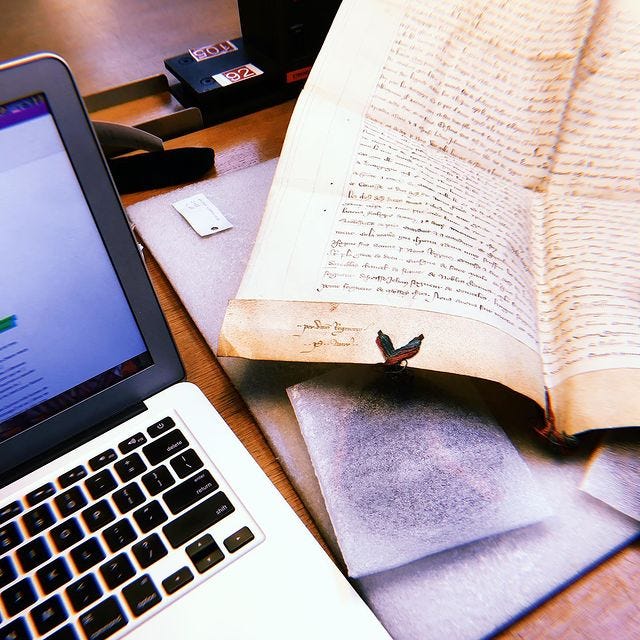

But, of course, the most annoying thing about microfilms is that, to someone haptic-prone like me, you don’t get to touch your documents. And if you don’t get to touch your fourteenth-century charter, have you even really seen it?

I realize that the opportunity to work on original manuscripts and documents is a privilege, even within the already restricted world of doctoral students and candidates. But I would be lying if I didn’t acknowledge that some of the most wonderful moments of my academic career were not fully related to the experience of encountering these artifacts and actually being able to hold them in my hands. Like when I gushed in the consultation room of the archives every time I saw a royal seal, how I almost cried when I saw Jeanne of Bourgogne’s large, red imprint, pristinely preserved. How I couldn’t stop looking at and taking photos of the green seal of Louis IX of France.

Arlette Farge, in The Allure of the Archives, captures this when she reminds us that there’s a physical or tactile aspect of flipping through pages of original documents (in her case, eighteenth-century records, primarily from the police) that allows the researcher to quite literally touch the past. And, as I grew more and more interested in the material aspects of life and of how identity was both created through and imprinted upon artifacts, it was hard not to be very aware of this very effect, of thinking “if a seal carries the identity of the sealer not just because of its image, but because of the physical act of stamping that image onto wax, then am I not in a way also touching something of that person by opening an archival folder and also holding this seal?”

There has been some discussion about the fetishization of the archives and of the archival material and how researchers need to be aware of placing that space and that object above analytical tools, because it is easy to get swept away by the emotional experience of being there and holding it. In my opinion, to be aware of this potential trap and to caution ourselves against it takes the researcher’s humanness more into consideration than less. It’s not about pushing away the emotional, sometimes visceral, reactions to the experience, but rather acknowledging them, understanding where they come from, and process them accordingly. For some, that will mean including these notes in the final piece of written work. For others, like myself, it will mean living with this unsettling experience of being in front of eight-hundred-year-old parchments and realizing that, despite all the work that has gone into preserving them, that encounter really does sometimes boil down to sheer luck—of it surviving and of you being able to see it.

Early in the fall semester of 2018, I was back in Paris for my research year. I was excited, the world of research was my oyster. I had a firm sense of how to navigate my way around both the national library and archives in Paris, I knew the collections I was going to be working on, and I felt confident about my ability to read French medieval scripts. Then one day in September, I came to the manuscripts room of the national library and requested a volume of copies of medieval documents created by a seventeenth-century antiquarian.

And I couldn’t read it.

To be fair to myself, it wasn’t as bad as that time two years before. A tiny bit of my logic brain remained activated enough to whisper “this is doable with a bit of time.” But the first blow of opening that paper volume and feeling like my eyes could never decode that flourished penmanship was enough to send me in a spiral of panic that made me rush out of the room and to the restroom to have a little cry about it and to frantically text Life Associate about what was happening. It didn’t help matters that a Big Name in my field was also in the reading room that day and had spotted me there. I felt, for lack of a better word, a complete and utter fraud—and one who was about to be caught in public at that. It took a prolonged lunch break in the nearest park, under a soft sun and breeze, for me to calm myself enough to go back into the reading room, take photos of those pages, and request the next volume I had set aside for that day.

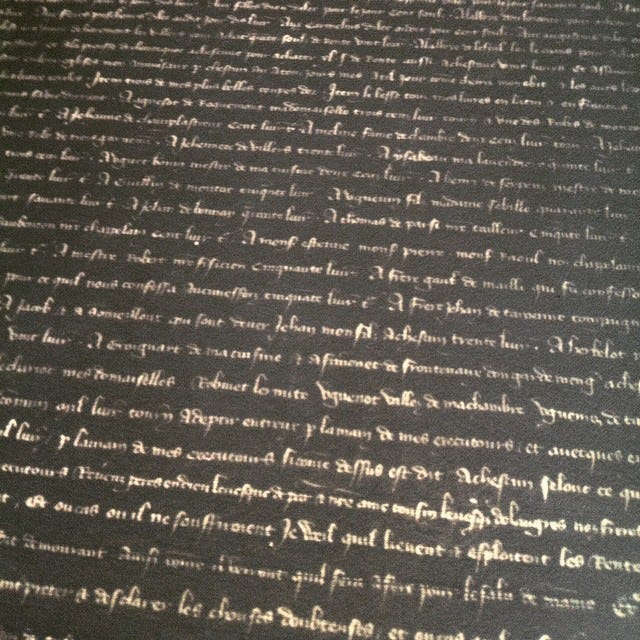

Medievalists often rely on early modern copies of documents, for a series of reasons. These could be the only surviving copy of a given document, which in French history had the pesky habit of getting destroyed by floods, fire, and revolutions (even with my restricted interests, I have encountered at least a handful of cases of each for medieval documents), not to mention the natural process of decay of parchment and, even more so, paper. They can also be handy when it comes to figuring out what place is where, since some toponyms changed throughout the centuries and some copyists would update the spelling of names of towns and abbeys and monasteries, bringing them closer to known modern appellations. They can be incredibly useful, or incredibly frustrating to work with, and most of the time they are both. One of the reasons for frustration, to me, came from having to learn new hands all over again, just when I thought I had a good hang of everything.

But I guess that’s another thing I miss about being in the archives doing research: there’s a constant reminder about how cyclical, rather than linear, life can be. A year later, already back in NYC, I would be easily collating the seventeenth-century copy along with the fourteenth-century original. Another couple of years later, I would be diving into eighteenth-century antiquarians like it was nothing.

And to this day, I can’t pass the opportunity to look at a manuscript and puzzle about what exactly is that one strange word on the third line.