Historical fiction, as a historian

On reading the first book of Maurice Druon's "The Accursed Kings" series

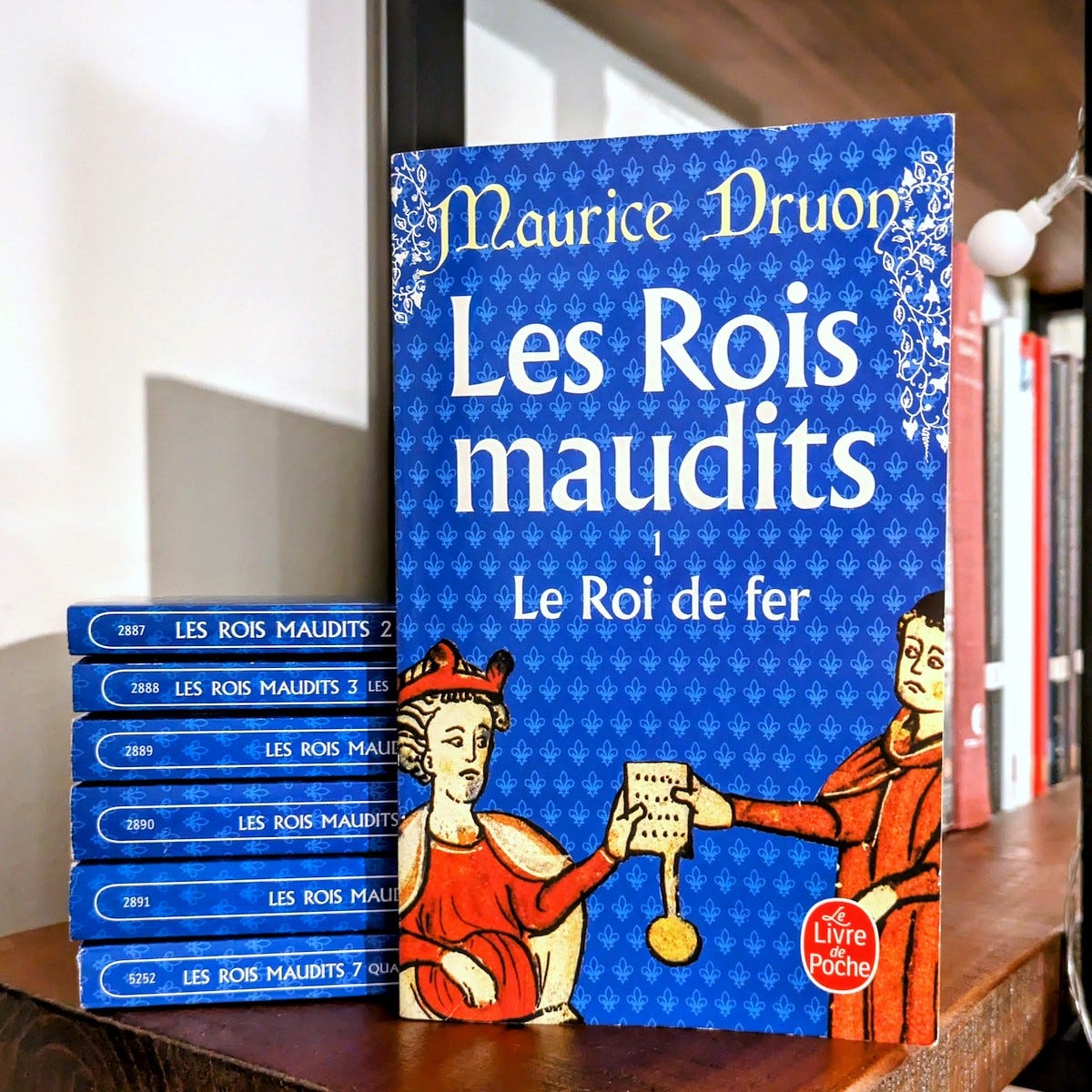

April began with me finishing the first volume of Maurice Druon’s series The Accursed Kings, finally getting to one of the many small projects I wanted to get to this year after buying the entire series in Paris last fall.

The Accursed Kings (or Les Rois maudits in the original French) is a series of seven books written by Maurice Druon (with the help of several authors and researchers, which he acknowledges in an author’s note) between 1955 and 1977, adapted twice as television series in France (in 1972 and 2005). The French edition of the first novel, Le Roi de fer (The Iron King), that I purchased is its 53rd (2022), and its popularity has been no doubt boosted in the past decade thanks to George R. R. Martin calling Druon his “hero” and penning the preface to the new English editions.

But what is the book about?

The year is 1314. King Philip IV of France, also known as Philip the Fair (for his handsomeness, not his sense of justice) reigns over a progressively united but still unstably-so France. In need of money, the king sets his eyes over the order of the Knights Templar, a military order that has become a trans-European financial powerhouse and the biggest creditor of the kingdom. Chasing, imprisoning, and torturing the French leadership of the order since 1307, the legal procedure against the order’s master is coming to an end when the series begins. After refusing to be incarcerated for life for crimes admitted to under torture, the master Jacques de Molay dies burned at the stake, his last words cursing the three men he saw as directly involved in his demise, to their thirteenth generation: King Philip, his counselor and Keeper of the Seal Guillaume de Nogaret, and Pope Clement V—all three of whom die by the end of the first novel.

Parallel to this, an adultery plot is discovered involving Philip’s three daughters-in-law: Marguerite and Blanche are found to have lovers, while Jeanne is guilty of aiding and abetting her cousin and her sister (yes, everyone was related and not just by marriage). The case, also known as the Affair of the Tour de Nesle (where the lovers supposedly met), leads to the imprisonment of the three women (including the future queen of France) by the end of the first Accursed novels.

When I went to Paris last fall, the one book (or set of books) I knew I wanted to get was the Accursed Kings series in its entirety. At one point, during my PhD, I had owned them all, read the first two (and a half), and felt like it was hitting to close to home to continue. I ended up selling the whole set, and had recurringly told myself that one day, I would get all the books again and read them all.

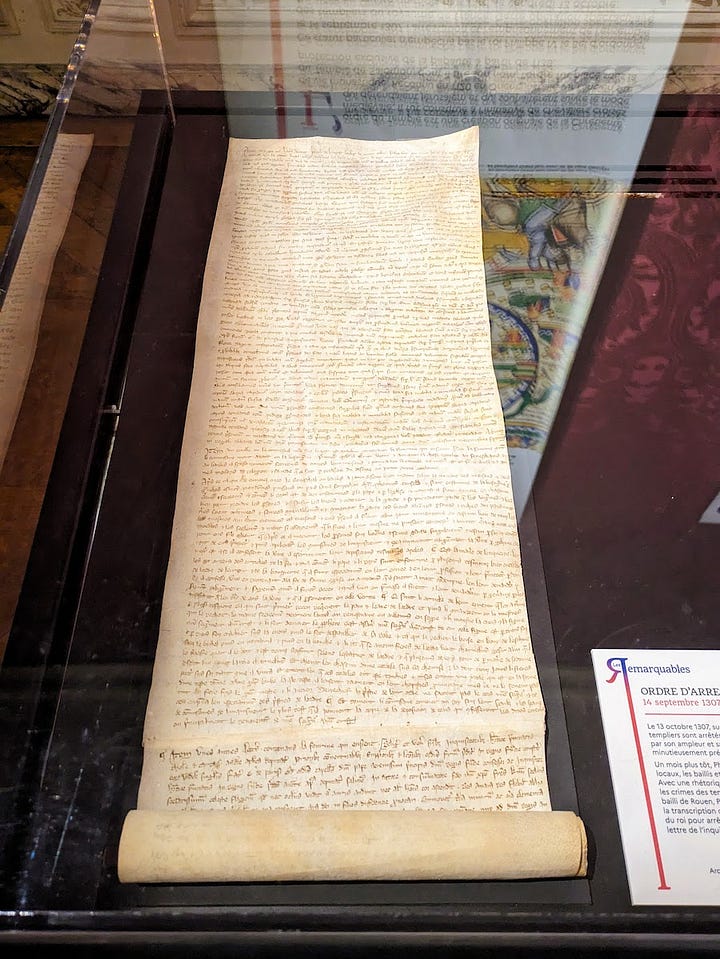

And even before I made it to the bookshop, I made it to the French national archives, and its exhibition on the process against the Templars—including the 22-meter-long scroll with the transcription of the testimonies collected during the procedure.

I may no longer be an academic medievalist, but I cannot say seeing it didn’t give me the shivers.

So I have to take this opportunity to share a snippet of it.

Le Roi de fer is not a deep novel. I would even venture that, unless you are very interested in medieval history or historical intrigue in general, it will probably not be an enthralling book, and I would be curious to see if Martin’s preface and the reissuing of the series actually made a significant splash.1 The characters are, for the most part, quite flat, without many surprises or layers to them (except for Philip IV and, perhaps, his daughter Isabelle, queen of England). There are several points of view throughout the 316 pocket-sized pages, but few feel like they offer a meaningful view into the respective voices. We get the dreamy Italian youth, the crafty ruffian, the calculating bureaucrat, the scheming princesses.

This lack of nuance was particularly difficult to manage with the three royal daughters-in-law. The novel clearly picks a side and it is not theirs. The young women are vapid, shallow, and vain, and there is no doubt as to their adulterous escapades, whereas the historical record is a lot less clear on the subject. And, considering how difficult it is for women’s history—even royal women’s history—to be well documented for the time, a little more grace might have been extended to these three young women (Blanche, the youngest, was around 18 in 1314; Marguerite was about six years her senior). But that would defeat the purpose of creating another character (Robert of Artois) as the unofficial hero, wronged by Jeanne and Blanche’s mother in regards to his succession to the county of Artois.

All disputes always boil down to the same things: land, power, authority.

Or, considering that everyone was cousins: everything always stays in the family.

There’s an ongoing joke that historians are the worst people to watch historical fiction with, and there’s a reason. It seems some of us become incapable of flicking the switch that allows us to join in a general suspension of disbelief, if this disbelief comes at the expense of what we hold true and dear and of what defines our intellectual and, to a certain degree, emotional selves. I can watch Andrzej Wajda’s 1983 Danton without a problem, even though I know it is highly anachronistic at times (zero emotional attachment to the French Revolution), but I could not bring myself to watch Riddle Scott’s 2021 The Last Duel (this piece by Sara McDougall and David Perry offer a glimpse as to why).

That is not to say I don’t have a heart. At least, I don’t think so. A Knight’s Tale (dir. Brian Helgeland, 2001) is a favorite of all time, a modern classic, and I will never hear otherwise. I may not have fallen in love with Lauren Groff’s Matrix, but I found the writing compelling and mystic in just the right way (even if I maintain that there was little “Marie de France” in a Marie de France-announced novel)—I was excited enough when it came out that I bought it in its hardcover edition, something I never do. A top read from 2022 was Silvia Townsend Warner’s The Corner That Held Them, which covers the lives (and disputes, both petty and grand) of nuns in a Norfolk nunnery. I’m not morally against reading Victor Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris, I just admit to being incredibly lazy.

But I’ll also admit to not being a reader of historical fiction. At least, not anymore. More than one person has already heard or read me saying that I became a historian of medieval France by being captivated by Jacques LeGoff’s biography of King Louis IX of France (at one point, I had two copies of the text in Portuguese, one fully annotated, another less so). What fewer people know is how I got into history in the first place. In Brazil, the university-entrance exams (vestibular) are subject-specific. Meaning: you don’t get into college and then pick a major; your entrance is tied to your choice of B.A. from the get-go. And my choice for History, across universities, was caused by my obsession with Bernard Cornwell's The Warlord Chronicles and then The Grail Quest novels, before jumping into and eventually abandoning The Saxon Chronicles (yes, the BBC/Netflix series one).2 Those novels made me want to study not just history, but medieval history, and not just medieval history, but English medieval history.

I’d say that, for plans made when I was sixteen or seventeen, checking two out of three boxes, in the long run, is pretty impressive overall.

That is all to say that I foresee a lot of shaking my head and double-checking to see if I am misremembering things or if it’s a matter of “artistic license,” but I shall persevere with these cursed kings. This might be the perfect time for this, really: while things are just fresh enough so I have a good sense of the background, but not so raw that I feel some type of professional duty towards those historical characters.

Or maybe I’ll read the remaining six volumes and wonder why I did it in the first place.

Books mentioned:

(disclaimer: I do not make money from the links below; they are provided as reference and shopping through them supports my local independent bookstore)

Maurice Druon, The Iron King (trans. from French by Humphrey Hare)

Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris (trans. from French by Alban Krailsheimer)

Bernard Cornwell, The Winter King (The Warlord Chronicles, book 1)

Bernard Cornwell, The Archer’s Quest (The Grail Quest, book 1)

Bernard Cornwell, The Last Kingdom (The Saxon Chronicles, now The Last Kingdom series, book 1)

On the other hand, as a medievalist who worked on precisely this period and crafted her project as not to deal with the Tour de Nesle affair, I can say that the opposite might also be true: if you are too deep into the historical and historiographical problems of the time, you might be ducking out every once in a while because, well, that is not really what we know from the sources…

It’s been well more than a decade since I have read any of these, so I have no idea if/how they hold up—but, if I’m being honest, I also have no desire to revisit them to find out.

I love historical fiction and I have always rolled my eyes at other historians' dismissive attitudes towards it. I mean, sure, most of it is not 100% accurate, but it's not a documentary, it's entertainment.

My biggest pet peeve is people complaining about the costumes in Outlander and how historically inaccurate they are. It's a show about time travel, for crying out loud, are you sure that it's in the costumes where you want to put an end to the suspension of disbelief?!?!?!?! If nothing else, of course a time traveling person would bring some of their 20th century ideas and practices to the past.

That said, I've never watched historical fiction about my super niche subject, so maybe that would change things!