In the in-between of languages

Exophonic writing, Brazilian literature (in translation), and inhabiting sentences

Recently, I came across the term “exophonic” and I was instantly fascinated. I spent hours ruminating it, mentally savoring how it sounded and the images it evoked.1

“Exophonic writers” are those who write in a language different from their mother tongue. In some ways, it is a phenomenon every single scholar of the Christian Middle Ages (to stick to what I know) encounters: Thomas Aquinas didn’t grow up speaking Latin, but he had to write in it.

But historical examples (which abound) do not represent something that feels to be at the center of exophony as explored today (and in the past hundred or so years). In the pre-industrial, pre-nation-state world, multilingualism was often a form of dilettantism (or, if we continue to keep Latin in the mix, an imperative in certain circles).

Modern exophony, prompted on the one hand by (forced) migration and on the other by the ever-growing flux of text and ideas, is also a statement of existing beyond the “orginal” local. It is a constant reminder of the potentially disruptive power of language in a world of national borders, especially when one claims a voice “not their own.”

There is some debate on how “exophony” is defined, whether it overlaps with bi- and multilinguist, whether languages acquired during infancy count towards this experience… I am not a linguist, so I can’t assess all sides of this question. I will cite Chantal Wright’s definition here:

Exophony describes the phenomenon where a writer adopts a literary language other than his or her mother tongue, entirely replacing of complementing his or her native language as a vehicle of literary expression. The adopted language is typically acquired as an adult; exophonic writers are not bilingual in the sense that they grew up speaking two languages, and indeed to not necessarily achieve the type of spoken fluency associated with the term “bilingualism.”2

I like this definition because it’s easy to understand. I like how it leaves so much room for the confusion, strangeness, and all in-between that gets lost in, and especially created by, a sort of internal self-translation that often precedes the page and the text itself.

And I like it because speaks to my experience as a person-who-writes.

It’s interesting to think that a lot of the conversation around exophony happens in literary terms. It makes sense that it is so—after all, literary expression is, in many ways, first and foremost a choice. Academic writing obeys a whole other set of rules, including the need for precision in vocabulary and to be understood by the jury of professionals who assess its validity.

In other words: I couldn’t have written my dissertation in a language other than English, as a PhD candidate in a US-based History department, but I could have started this Substack project in Portuguese. It was a choice not to.

At this point, it is hard for me to separate the writer from the language. To take myself out of English to express ideas in long-form writing. Not because I have forgotten Portuguese (I haven’t, even if I have lost touch with most of current slang).3 But because I have become a person-who-writes primarily not in Portuguese. With the exception of my honor’s thesis and a short article published as an undergraduate, all my writing as a researcher was done first in (really passable) French, then in (variously acceptable) English. And my online life has been much more Anglophone than anything else for more than a decade, as I navigated and explored different fandoms as a teenager and young adult while also trying my hand at writing short fanfiction stories for fun. I could even venture to say that I took English classes in person to learn the language structure, but being online is what taught me that I could have fun with it.

Some would say that I—as many non-native Anglophones writing in the US—had to learn a lot of what qualifies “proper academic English writing” along the way.4 I would have said so too some years ago. Now, I would say that my experience involved much more unlearning Latinate structures, shedding a lot that I wish I hadn’t for the sake of clarity, since the academic setting is not one necessarily open to the idiosyncratic nature of writing.5

The exercise of making my long sentences—full of parenthetical and subordinate clauses that make perfect sense in Portuguese—fit into the more straightforward syntax of English was one full of struggle. In this sense, it perfectly mirrored (and added to) the struggle that writing my dissertation ended up being. A lot of chopping—sentences, ideas, images—, separating different blocks of meaning that made perfect sense in my head but that needed to be streamlined differently for an audience of not-me.

This week, I had the opportunity to attend a round table celebrating and discussing the translation of Itamar Vieira Junior’s Torto Arado, titled “Crooked Plow: Translating Social Justice in Brazil.” It is just one of the many events he is doing in the US following the publication of this translation (including one at the NYPL). The event was hosted by The Society of Fellows and Heyman Center for the Humanities and the Public Humanities program (Columbia University). Alongside the author were Johnny Lorenz, who translated the book into English, and Prof. Keisha-Khan Perry, who gave a short talk titled “The Political Urgency of Translation.” It was a wonderful event, before, during, and after which I had the chance to hear all these different Brazilian accents I don’t often hear here, all in one room alongside Lusophiles and newcomers. While I sat there, thinking about the potential of ideas and feelings to breach the common barriers of language, I was energized in a way that I hadn’t been in quite some time.

This is probably where I pause to say that, I am beyond happy that so many Brazilian authors are reaching international audiences thanks to translations.

Bruna Dantas Lobato’s translation of Caio Fernando Abreu’s collection of short stories, Moldy Strawberries, was longlisted for the 2023 PEN Translation Prize and her translation of Stênio Gardel’s novel The Words That Remain is a finalist for the 2023 National Book Awards.6 Clarice Lispector is something of a darling in certain circles of bookstagram and the translations of her work published by New Directors Publishing are sure to catch anyone’s eyes in a bookstore. Mario de Andrade’s Macunaíma, a novel that in many ways founds and synthesizes Brazilian modernism, has received a new translation by Katrina Dodson, which was discussed in an event with the translator at the NYPL and is part of a story on the author by Larry Rohter in the 5 October 2023 issue of the NYRB. The Penguin-published translation by Flora Thomson-DeVeaux of The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas, by Machado de Assis (my favorite Brazilian author of all time), was sold out a day after its release in 2020 on both Amazon and Barnes and Noble. The newest issue of the NYRB brings a piece by Charlie Lee on Victor Heringer’s The Love of Singular Men, translated from Portuguese by James Young and published last month by New Directions Publishing.

And that is to speak only of the literature books that come to mind while I take a sip of water.

And, after that, sip I should make another pause to add that I haven’t read most of these translations (the one exception being The Posthumous Memoirs). Whenever I read something in translation from a language I know, I feel my brain trying to deconstruct the translation process, back into their original structures.

I guess you could say after all these years living outside my native language, I am searching for a way to protect my experience of Brazilian literature as an endophonic one.

Something whose beats sound primarily in my heart’s ear.

In my ideal world, “exophonic” would mean what the word first called to mind: something that produced an external sound. For writers, I thought of “those who speak their work.” Reading was, for the longest time, a not-silent experience, so I think there’s potential in thinking about out-loud composing as well.

A lot of my editing and learning process involved having text-to-speech software recite my paragraphs back to me. Something about the mechanical voice being unable to inflect sentences as I would if I were reading them allowed me to get some distance from the text, from my mental voice, and see how others would perceive it, its argument, the cadence of evidence and its unpacking.

Maybe this is the point where I state that some of the lessons I have learned have stuck. I try to avoid the passive voice (though it can be so useful).7 I am careful about how many conjunctions I employ in sequence and I pay extra attention if referents are clear when I’m using a lot of pronouns. It made writing a little less a spur-of-the-moment thing and more of a deep-breath-and-check-yourself thing

And even with all that—or perhaps because of that—, to me, the choice of writing in English as a way to reclaim my joy in writing was a no-brainer. I don’t want English and its syntax to get the best of me. I want to remember what it’s like to have a voice in this language that has meant so much to me. But I also want to remember what it’s like to dance around commas, rejoice with semicolons, and be suspended in the air with ellipses. I want to express myself to the friends I have made along the way on this journey that has been as tortuous and winding as my sentences.

If I can’t ever bring my non-Anglo heart into this, what’s the fun in that?

Important PS:

Most of this newsletter was written before the Crooked Plow event took place, but I need to make note of one of those coincidences in life that just make everything a little more magical.

During one of her interventions, Prof. Perry mentioned, somewhat jokingly, the difficulties of translating French, Spanish, and Portuguese texts into English because sentences in those languages can just go on while they cannot in English.

The room burst into a soft giggle. I, on the other hand, felt my face burning.

Guilty as charged.

Words are, of course, funny in their own way, and I can’t seem to resist them on occasion. “Holographic testaments” are those effectively written by their author, unlike dictated documents. “Holograph” as a noun (a document in the handwriting of its author) comes from Greek and has been attested in English since the seventeenth century. “Holograph” has absolutely no bearing in the rest of this text, except as an illustration of how my imagination sometimes gets the best of me even when I know better: Working on premodern last wills and testaments for my dissertation, whenever I encountered the expression “holographic testament,” I would immediately imagine something out of Star Wars or Star Trek (take your pick).

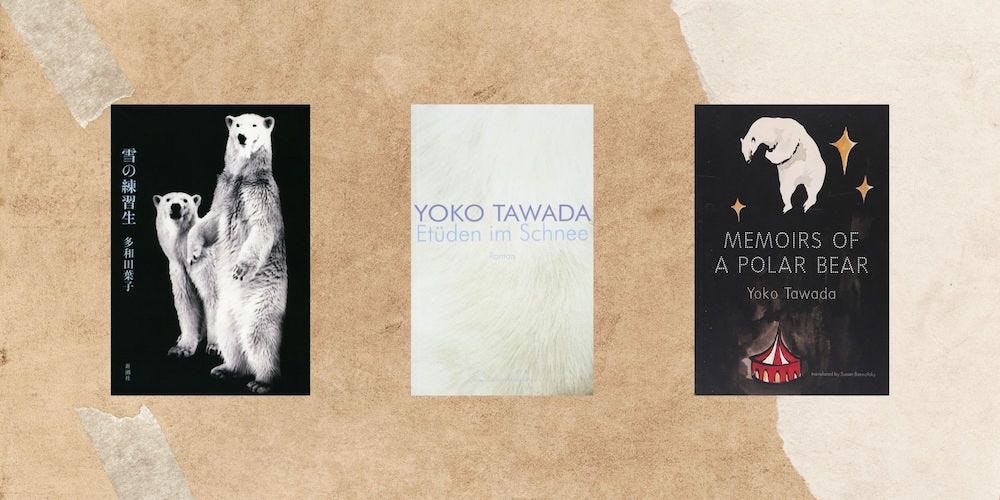

Chantal Wright, “Introduction: Yoko Tawada’s Exophonic Texts,” in Yoko Tawada, Portrait of a Tongue, trans. Chantal Wright (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2013), 2.

Cursing in Portuguese remains very cathartic.

I don’t want to get into what constitutes “proper academic English” and I think it will suffice to say here that it is, of course, an incredibly classist and racist construct in itself.

I still remember—and probably will remember forever—when a professor said my end-of-semester paper (which I wrote entirely and directly in English) read like it had been translated, with no adaptations, from a Latinate language into English. What I think he meant to say was: Your sentences are too long and hard to follow with the structures we have at hand. What I heard was: You do not know how to do this.

She is herself to be added to Wikipedia’s “dynamic list” of exophonic authors, with published short fiction in English and a novel coming out simultaneously in English and Portuguese (in her own translation) next year.

It was very interesting to me to find “to disappear” in the passive voice across Megan McDowell’s translation of Mariana Enríquez’s Our Share of Night. Not because of the strangeness of the construction, but because it triggered me, at every instance, to think of the shared political experiences in the Southern Cone and beyond, of a historical uncertainty that remains at the center of so much trauma in the region.

I just loved this! Thanks for sharing!

This is such a beautiful essay. I love how you weave together the personal with the more academic subject. I learned so much! 💕