interregnum

On transitions, on being stuck in the middle, on maybe not going anywhere specific

This post is dedicated to E., who said she would get back to writing when I did.

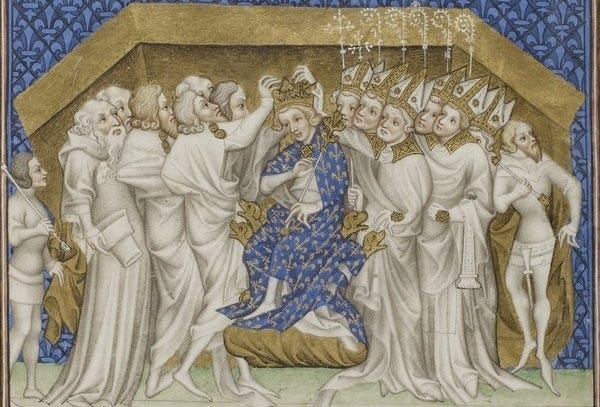

An interregnum is a period of transition between, say, the death of a monarch and the rise of their successor. It was something of a common situation in the early history of European monarchies, when the successor of a ruler was not given by birthright (even when assumed), but had to be confirmed and affirmed. This was before the principle of hereditary succession truly took root, when the eldest child (or son, depending on the rules), of the deceased monarch would automatically become the new ruler, even before a ceremony of coronation took place.

I say “early history” but, in fact, the practice of hereditary and non-hereditary successions can and have been concomitant throughout the centuries, all the way to the 21st century. Take, for instance, what happened in the United Kingdom when Queen Elizabeth II passed away: Charles was immediately acknowledged as the new British monarch, even if it took months for him to be crowned in Westminster. On the other hand, the Vatican—an elective monarchy—experiences periods of interregnum after each and every death of a pontifex, as the rules of succession demand an election, which usually takes some time to be organized. In the case of the Vatican, it receives a special name, sede vacante (meaning “empty seat”), but the content behind it is the same: a crown and a throne without a king, a forced period of suspension and uncertainty.

I could write more about medieval monarchies because the information is still out there or in here, swimming in my brain and coming up for air more frequently than I would care to admit. But I won’t.

Instead, I want to hold in my hands this sense of suspension and uncertainty, nurture it for a bit, share it with you, as it’s been my companion for some time now. So much time, indeed, that it feels like a companion, one I’m not sure I treasure but who I’ve come to know almost intimately. The interregnum is a dramatic period of political transition; meanwhile, life is full of them.

A little over a year ago, still in New York (or rather, back from Rio to New York), I reminisced about closing cycles: “What I know now is that one [cycle] always begets the other, whether we like it or not. Sometimes, it is hard to adequately understand what those mean, or how to live fully the liminal moment where one hasn’t quite yet become the other. In more ways than one, here I am. One cycle finished. Another still yet to come. Lost in liminality, if you will.” Little did I know that I would be here, several months after, still feeling myself in shaky ground, but also looking around and seeing so many different cycles closing, being reminded that sometimes life has this way of pushing you forward, even if you don’t really know what that means or what it will do to you.

In anthropology, the ritual is traditionally understood to follow a tripartite structure according to the hugely influential (and, of course, highly controversial) systematization by Arnold van Gennep in the early twentieth century. According to this perspective, every ritual, across cultures, can be organized into three phases: the preliminal phase, which includes a separation from “life as you know it”; the liminal or transitional phase, during which the actual rites take place and the new identity of the participant is established; and the postliminal phase, which marks the reincorporation of the individual, now baring a new identity, into the group.1

Some decades later, Victor Turner would reinvigorate this view of rites by emphasizing the liminal phase as a moment when the individual finds themself suspended from any and all affiliation, “betwixt and between.” This suspension of rules, of ties, and of time, in a way, was easily adopted by different corners of the humanities, serving as a quick hand for different processes of transformation and status changes.2

The structure of separation from known life, suspension of rules, and reintegration as a new person might sound familiar if you, like me, had an adolescent interest in Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces and its monomyth proposition.3 It does, in fact, map out quite neatly onto the traditional hero’s journey, and it’s not a stretch. Campbell himself neatly sketches the relation in the introduction: “The standard path of the mythological adventure of the hero is a magnification of the formula represented by in the rites of passage: separation—initiation—return: which might be named the nuclear unit of the monomyth.” (28)

Campbell’s allure hasn’t been necessarily beneficial for pop culture (an influence magnified by the success of one of his most famous movie-maker followers, George Lucas). But it is undeniable that a whole lot of the pop culture I have consumed as a Millennial has been informed by and structured around the hero’s journey, whether knowingly or not.

The hero’s journey is alluring as a pattern for the creation and consumption alike because it falls neatly into the easy, Aristotelian narrative structure of the arc. The protagonist departs from a point of more or less stagnation once something propels them forward, the story and its conditions swelling towards the climax, leading towards the resolution; then our heartbeat returns to normal and the protagonist returns to stability. They may be a little smarter, a little moodier, a little or a lot changed, but the important thing is that they regain their footing, having a better sense of themself and the world surrounding them. Alternatively, they may find that the breach between who they are now and the world they left behind at the beginning of the journey is insurmountable, socially (and sometimes effectively) killing that other individual to leave them behind.

We have laid down that tragedy is an imitation of a complete, i.e. whole, action, possessing a certain magnitude (There is such a thing as a whole which possesses no magnitude.) A whole is that which has a beginning, a middle and an end. A beginning is that which itself does not follow necessarily from anything else, but some second thing naturally exists or occurs after it. Conversely, an end is that which does itself naturally follow from something else, either necessarily or in general, but there is nothing else after it. A middle is that which itself comes after something else, and some other thing comes after it. Well-constructed plots should therefore not begin or end at any arbitrary point, but should employ stated forms.

Aristotle, Poetics (trans. Malcolm Heath)

Don’t we all just wish all our journeys were like that? That, once home—the old one, or a new one, it doesn’t matter—we could look back, see a clear wave that brought us to this shore we now inhabit, the waters receding but leaving behind clear paths and clear meaning. That we could turn to ourselves in the mirror, in our diary, to our family, and say, “this is why I left, this is what happened along the way, this is what I gained and lost, this is who I am now.”

But often that is not to be. Too neat a structure to explain life, I suppose.

You may think that the reason why I am bringing all of this up is because of my own current liminal status or my hardship in dealing with it. You would not be wrong, but you wouldn’t be fully correct either. It seems that the old saying of when it rains, it pours is true. I find myself pondering not only over my own transitions in life, but of a handful of people close (and not so close) to me, as they tackle big status changes that are not mine to discuss in public beyond these general terms. Let them stay here as they are, a stand-in for your Difficult Changes as well, so that I can excuse myself for not going into details, and so that you can see yourself reflected and considered here if you so choose.

Since its inception, Juliana, cronista has been dedicated to dealing with this sense of lack of certainty, brought to the doorstep of my mind as I had finished a one-year contract after finishing an eight-year PhD and deciding I did not want to pursue the traditional, expected path of academic job hunting. What was left was a whole lot of questions about who I was then, if not a practicing academic (I call myself a “recovering academic” for now), dedicating my life and mental energy to my research. It’s been over two years now. That gave me a whole lot of time to think, which was not so great for a hundred little reasons, the most important being that I am and always have been an overthinker to begin with. Onward went colleagues towards positions, friends from back home with their careers, stuck I stayed, feeling like quicksand was under my feet at all times. Move a little, sink a little.

Wasn’t life supposed to be about moving ever forward?

I heard about Jane Alison’s Meander, Spiral, Explode4 during a talk between Polly Barton and Liza St. James on the occasion of the release of Barton’s translation of The Place of Shells by Mai Ishizawa.5 They were discussing the topic of narrative structures and the possibilities of non-linear narratives when Alison’s book was brought up. I furiously typed the title on my phone’s note app, curiosity piquing because, wow, wasn’t that a title. I purchased the book not long after the event, but it sat unread for a few months until I got to it last month, when it felt just right.

Alison’s essay is not about life writing, not in the self-help sense at least. Meander posits that, the Aristotelian dramatic arc (beginning, development, end) may have informed much of writing and of writing about writing for I-don’t-know-how-long but such mindless adoption of this model fails to acknowledge that, firstly, Aristotle established it as a model for drama, not novels (which he absolutely knew nothing about since it hadn’t even been invented), and that, secondly, there are many other patterns that our human brains recognize as natural and have already been explored by novel writers.

I don’t know how innovative Alison’s points are, as I’m not nearly as familiar with the theory of the novel as I would like to be. But I do know her book is quite welcoming to non-specialists, and that it organized, in a way much neater than I ever could, the non-traditional narrative structures I am growing more and more fond of. It was also a nice reminder that there are different stories to be told other than the one of event-climax-resolution—in nature as in fiction, there’s more than arcs and waves.

In a very cool examination of Turner’s paradigm (which we can perhaps quite easily associate with the Aristotelian dramatic arc), the historian Caroline Walker Bynum6 shows how the comparison of narratives of exceptional (medieval) lives to the ritual process (and the emphasis given to the central role of liminality in it) only really work on narratives written by men—whether about other men or even women. Women, on the other hand, when speaking of other women or about themselves, do not follow this “traditional” narrative structure, seeing these lives as always already liminal (because of the marginality imposed by their gender) and thus not following a clear developmental path from crisis to resolution. Because (medieval) women are always already liminal or peripheric, they are never pushed out of a given structure in a dramatic arc towards a heightened status.

I don’t mean to recap her entire argument here, because this is not a piece of academic writing (I swear). But when reading Alison’s essay, this article came back to me again and again (to the point where I had to find my copy of it and, when failing to do so, ask a friend7 for it). I can see a similar pattern, or lack thereof, when it comes to the absence of a clear linearity towards resolution in so many of the books that have stuck with me in the past handful of years. To name a few: Territory of Light (Yuko Tsushima, trans. Geraldine Harcourt), The Forbidden Notebook (Alba de Céspedes, trans. Ann Goldstein), The Wall (Marlen Haushofer, trans. Shaun Whiteside), Small Things Like These (Claire Keegan). All, in their different ways and voices, tackle the humdrum life of not much, the repetition of rhythms, a sense of stagnation that might come from it all.

The interregnum, the ritual process, the hero’s journey, the dramatic arc: all of these systems necessitate a neat conclusion, a clear marker that the end of a process has been reached, balance has been reinstated, we can all breathe now.

But in life, as in nature, there are other patterns. And I find myself meandering, spiraling, perhaps exploding, much more than reaching a clear shore as the wave breaks.

And that will be okay.

Arnold van Gennep, Les rites de passage. Paris: É. Noury, 1909.

Victor Turner, The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977 (1969).

Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New York: Pantheon, 1949.

Jane Alison, Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative. New York: Catapult, 2009.

Mai Ishizawa, The Place of Shells. Trans. Polly Barton. New York: New Directions, 2025.

Caroline Walker Bynum, “Women’s Stories, Women’s Symbols: A Critique of Victor Turner’s Theory of Liminality,” in Anthropology and the Study of Religion, ed. Robert L. Moore and Frank E. Reynolds. Chicago: Center for the Scientific Study of Religion, 1984, 105-25. Re-printed in Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion. New York: Zone Books, 1991, 27-51.

The aforementioned E. from the dedication. Thank you once again for the copy!