Like the good recovering historian of medieval France that I am, I couldn’t help tuning in to watch the grand reopening ceremony of the Notre-Dame of Paris last Saturday

How could I not? In some ways, that enormous church has been more part of my life than any other church I have ever walked by (since I’m not a churchgoer and I don’t even know where I was baptized, though I know I was). But as with some good stories, this one should start from the beginning. Not from its construction, because I’m not going that far. But the memories of my first encounter with it. And like so many stories, it sort of takes a life of its own once you start pursuing it.

This is this story: of a cathedral, of an architect, of fire, and of light.

My first graspable memory of the cathedral comes from a little over two years after my first visit to Paris. I arrived in the city in early October 2011 for my M.A. My mom came with me, to help me sort things out and settle in as best as possible in a sixth-floor walk-up (which, in US terms, would be a seventh-floor walk-up), which you reached after climbing a never-ending set of spiraling stairs. Most of our days then were spent under usual fall weather conditions in Paris: gray skies, a type of gray I would get very used to in the following years because of how persistent, almost relentless, it could be for days on end between early fall and early spring.

In one of the few days we took for not getting my studio ready, I took my mom to the Île-de-la-Cité, the island in the Seine where it all began, where the official center-point of the city is and where both the Sainte-Chapelle and the Notre-Dame are located. We visited the former first, taking advantage of some very shy sunlight shining through the clouds to appreciate the stained-glass windows in all their colorful magnanimity. After lunch, going towards the Notre-Dame, we noticed an enormous line formed. The Notre-Dame has never been not busy, but that was nothing like I had seen before, so I went to check what the small red sign by the door said: It just so happened that it was the first Friday of the month, and at 3 PM a mass would be celebrated in honor of the Passion relics housed in the Notre-Dame.

As I’ve said, I’m not a churchgoer. But I had come to Paris to do research and write my thesis on the Sainte-Chapelle. So yes, I waited in line, and I saw the reliquaries being brought out, and I watched the mass (of which I understood very little if anything). It wasn’t a religious experience, but it was in some ways a spiritual moment. I had so many doubts, so many questions, so many uncertainties about moving across the Atlantic on what felt like a whim, to live and read and write in a language I still felt very green about (not knowing I would do it all over again in less than three years). And there I happened to be, at the right place, at the right time, in what felt like a sort of welcoming gesture of the world, letting me know that sometimes things just happen, in a good way.

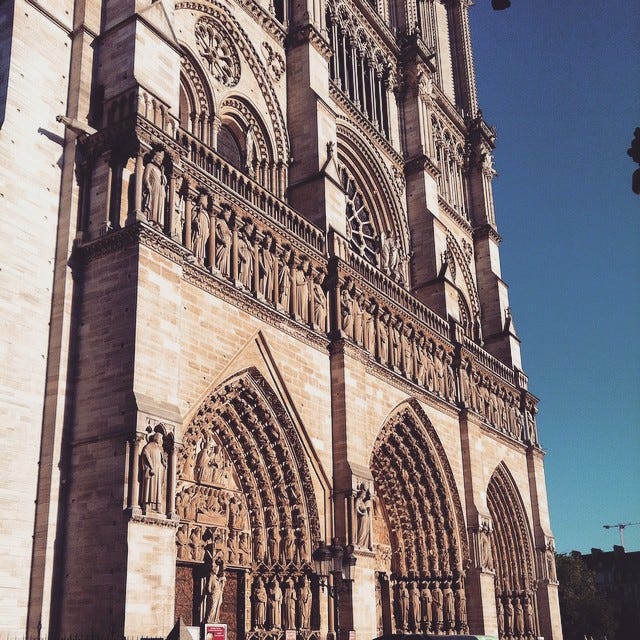

In the following years, walking by the Notre-Dame would become part of my routine. I would come to see the portal with the scene of the coronation of the Virgin with the excuse that I was writing about it, but really, I just wanted an excuse to follow the movements of the arches and folds. But I was really in love with how it all looked at nighttime. I would grow attached to how the external lighting made that colossus of limestone stand out against the night sky, yellow-and-pink-and-light-gray white against black.

One of my favorite things to do in Paris was cross the Seine behind the Notre-Dame. A good monument is a spatial experience, allowing you to admire it from different perspectives. Yes, the façade is beautiful, but have you ever appreciated its backside, the choir framed by the flying buttresses, an unimpeded view of the bronze spire against the sky?

The Notre-Dame, like so many medieval churches in France, is in many ways a survivor. Throughout the sixteenth-century religious wars between Protestants and Catholics and the French Revolution (and riots in Paris in 1830), many religious houses were targeted in various ways, leaving marks that go beyond the typical passage of time. In the case of the Notre-Dame, one of the most famous scars inflicted on it during the Revolution was the destruction of the “gallery of kings,” a series of statues of kings placed on the façade that were interpreted by the revolutionaries as a genealogy of French kings (when it was in fact a series meant to represent the kings of the Old Testament), and thus variously pulled from the façade and destroyed. The ones we see today are mostly nineteenth-century products, while tourists in Paris can still see some of the fragments of the original statues in the close-by Musée du Moyen Âge, in an airy and well-lit room that evokes open space more than most museum spaces.

Most of the medieval and early modern engineers and architects—or their equivalent—are unknown, but the name of one nineteenth-century architect looms large over both the Notre-Dame and some of her sisters who had to be “salvaged” from the destruction caused by the Revolution and the lack of care that followed it through the first half of the century: Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc.

In 1844, at the young age of thirty, Viollet-le-Duc was charged with the restoration of the Notre-Dame with fellow architect Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus.1 The work of restoration is one fraught with debates, and Viollet-le-Duc tended to espouse a vision of it that prioritized the “spirit” over technicalities such as “historical accuracy.” It doesn’t mean that he did not try. His interventions there and elsewhere were based on research, both in sitio and through iconographic archives. But sometimes you just have to make it better than real, I suppose, and being in charge of such projects Viollet-le-Duc was in the best position to do just that. While the quality (technical, artistic, historical) resulting from this approach can be discussed (and it was certainly so even during the progression of the work), it is undeniable that it is Viollet-le-Duc’s Notre-Dame that most people visualize and see in pictures or in person, one that maintained several of its medieval features, riffed off of them, replaced destructed features, and tried to erase some later additions in favor of a “purer” Gothic form.

In many ways, that meant creating a fantasy: the Notre-Dame of Paris, like many other churches and cathedrals still active in Paris and beyond, was not the product of a single, coherent building campaign that designed it from beginning to end without any later interventions, additions, and alterations (the main building campaign alone lasted almost two hundred years, between 1163 and 1345). Viollet-le-Duc’s (and our) Notre-Dame pretended to be more truthful than the building that already stood there, dilapidated surely but living throughout the centuries and the revolutions, accruing scars and tattoos and new adornments.

Or, in his own words,

“To restore a building is not to maintain a building, to repair it, or to rebuild it, it is to reestablish it to a state of completeness that may have never existed at any given point in time.”2

In October 2018, I was again in the city, this time doing research as a doctoral candidate, a little more sure of my French (but not of my English), and I saw the announcement for a set of lightshows that would “animate” the façade of the Notre-Dame. It was cold, it was almost rainy, it was crowded, yet I remember it so fondly because it was just incredibly fun. My favorite part was the moment when the light mapping recreated what might have been the full polychromic splendor of the façade (did you know the Notre-Dame, like many other Gothic cathedrals, were painted, and bare-stone colored?). I overheard someone not far from me laugh and ask their company “can you imagine if that was really how it looked?” For a few seconds, as the lights shone bright blue, red, yellow, I almost could.

Fast-forward to April of the following year. After a month of events that shook our family, I had swung back into research, full-throttle, and had finally started taking trips to local archives, trying to enjoy some of the countryside along the way as it moved past the train windows. I got to Dijon on a quasi-sunny Sunday, got lucky with an early check-in at the hotel, went out for lunch, a walk around town, a visit to the Musée des Beaux-Arts, and on Monday I went out to the archives, to confront mostly fifteenth-century documents that would not even end up in the final product of the dissertation. The medieval and early modern archives are housed in a fifteenth-century private hôtel-turned-seat of the city council. The main reading room, which was used as the meeting room for the council, hosted a concert by Mozart in 1766 (as proudly registered in a plaque by the old fireplace). It was a cold building, as many historical libraries and archives in France were, but something about the wooden panels, and decorated ceiling, and the archival material made it warm for me. I left the reading room that Monday feeling tired, with hundreds of photos on my camera to properly label and transfer to my computer, and I couldn’t wait to come to the hotel, do just that, and take a relaxing shower.

So you can imagine how I felt when, sitting in front of my computer, making sure I hadn’t missed any shelfmarks for the day’s work, I started getting message after message asking me if I had seen what was happening in Paris. I got on Twitter (R.I.P.), I got on YouTube, I turned on the TV, and my eyes couldn’t believe what was happening. 15 April 2019, nighttime hadn’t yet come to Pairs, the skies were still light blue as sunset was still a few hours away, and but dark grays crowded around the Île-de-la-Cité: the Notre-Dame was on fire.

On 2 September 2018, I was getting emotionally ready for my year in France doing research for my dissertation, living the excitement of the last couple of weeks before boarding, and making sure that whatever I needed would make its way into my two large pieces of luggage or my carry-on. Despite the state of chaos that our tiny NYC apartment was in, that day I took a long walk in the sun (even though it was too warm for my taste) with some iced matcha and we found our way to our couch to sit at the end of the day, have a glass of wine, and watch or play something. Things were hectic, but they were moving along just fine, and we were looking forward to the next eleven months despite everything.

Then my notifications pinged, and there I was, watching the Museu Nacional in Rio aflame. In one of the longest hours of streaming news, the former imperial residence in the middle of a gorgeous park (called Quinta da Boa Vista, literally “estate of the good view”), one of the oldest museums in Brazil, one of the largest in South America, one of the largest historical-anthropological collections in the world, was mostly gone. Faulty electric wiring; overheated AC systems; absence of fireproofing measures. A list of causes would come to light in the following weeks and months, none too surprising to anyone who had visited the museum in the past couple of decades with an eye for detail: it had been clear for quite some time that the museum had been struggling with lack of resources to adequately hold and exhibit much of its materials.

The Museu was part of my childhood and early adolescence. It was there that I first saw antiquities (Egyptian, Grego-Roman), ethnographic collections, the bones of one of the oldest humans ever found in the Americas (affectionately called Luzia). I was struck by the large neoclassical building, its creamy yellow exterior, and the large Bendegó meteorite that welcomed visitors. Later, throughout college and beyond, I came to understand and appreciate all the things not seen in cases: the archives and research collections, the body of researchers working there, the central role it played in so many fields.

And so, on 2 September 2018, I went to bed with a strange sense of defeat.

The destruction of cultural heritage hurts, be it accidental or intentional, on various levels. It always hurts, it always touches on something within me that led me to my history degree, that leads me to literature, that leads me to museums and art exhibitions. But we cannot pretend that the two events had the same significance to the world. Regardless of how they touched me, it is undeniable that there’s a significative and destructive imbalance in both situations. The path towards reconstruction after the events highlights this difference of attention and awe that they caused in the broad public. I would venture to guess that while most people somewhat connected to the internet in those two years heard about the Notre-Dame, a significantly smaller number was aware of what happened to the Museu Nacional (unless they were Brazilian, had an interest in Brazilian culture, or orbited the museum-world sphere). And that is just an infinitesimal example of the kinds of attention given and not given to the loss of cultural heritage around the world: some quickly garner millions of dollars, others are left to fend for themselves.

Materially and culturally, it is impossible to even measure the destruction caused by the fire in the Museu: collections totally or almost totally lost, a destruction that goes far beyond the architectural and structural effects. Meanwhile, the fire in the Notre-Dame brought about a lot of pearl-clutching, but not a whole lot of understanding that the cathedral was already a patchwork of various interventions. Irreplaceable losses, for sure, but not the church’s first, not the erasure of entire archival documentation, of research materials.

So, even as I celebrated, alongside the world, the reopening of the Notre-Dame of Paris on 7 December 2024, it was difficult not to think of museums shut, libraries destroyed, under water, under rubble.

Conservation, restoration, reconstruction: choices where the political and the aesthetic come together and intertwine in such ways that it is impossible to separate them. In the immediate aftermath of the event, Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiro de Castros, a researcher associated with the Museu’s anthropology department, expressed his wish to “leave those ruins as a memento mori, as memory of the dead, of things dead, of peoples dead, of archives dead, destroyed in the fire.”3 A hard political stance on the degradation of research and museological conditions, but also an aesthetic one, calling forth the forceful presence of the ruin as a visual and material statement, one with a long history in Western art and philosophy.

Another side of the coin: modernization. The fire in the Notre-Dame had hardly been quelled when President Emmanuel Macron announced that the cathedral would be open again within five years, and several modernization projects began to be proposed as a way to bring the Gothic church to the twenty-first century. Not by chance Viveiros de Castro also vents his disagreement towards “pretending that nothing happened and trying to put there a modern building, a digital museum, an Internet museum.”

Two positions that are not unfamiliar to the very history of the Notre-Dame, in fact. Already in the nineteenth century, when Viollet-le-Duc set out to restore Gothic buildings like the Notre-Dame, many raised their voices in favor of leaving the buildings as ruins, embracing the history that was written in their stones even if this was a history more of destruction than of conservation (if restoration was a new word and practice in the 1840s, conservation is not even featured in Viollet-le-Duc’s Dictionnaire). In the early twentieth century, French sculptor Auguste Rodin was still raising his voice against the nineteenth-century restoration campaign, claiming that the French churches submitted to such works had been robbed of real artistry in favor of a sterile completionist approach.4 He found the new artistry used to emulate the medieval to be lacking in feeling and in technique.

It is hard today to even imagine what the Notre-Dame would be like without Viollet-le-Duc’s interventions. Its decorative gargoyles, pictured and reproduced everywhere, used by Disney in its version of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, are mostly of his invention.5 The spire, which so many of us saw crumbling in 2019, was entirely a design of his, and claimed as such for all eternity by one conspicuous if curious signature: one of the twelve bronze apostles distributed around it bears the architect’s own face.

And, despite the fire and the destruction of the spire, this signature will remain in place due to a fortuitous coincidence, or perhaps in an act of divine intervention, that saw the twelve apostles being removed from the roof for restoration just days before the fire.

Not only that, but the project used for the restoration of the cathedral ultimately followed precisely that nineteenth-century project envisioned by Viollet-le-Duc because of its historicity. Almost two hundred years made it so that his Notre-Dame became the default Notre-Dame.

But I have to say one last personal thing. As I was watching the ceremony, I couldn’t help but feel shocked by how white and bright the interior of the cathedral looked. It was a combination of factors: the thorough cleaning of the years of dirty and soot (plus the untold amount of the latter caused by the fire) and the extensive and extreme use of spotlights and light cannons to illuminate the nave for the event. It looked nothing like I remembered, so radically different from the moody and dramatic atmosphere of the October day in 2011.

And in that moment, I may have had to agree with Rodin, who found modern sensibility failing to capture what gave the Gothic so much of its strength: the manipulation of light and shadow by the material forms and volumes, luminosity and darkness mingling, playing around each other, giving life to stone, steel, and glass.

One of the biggest proponents of the restoration of the Notre-Dame was, probably unsurprisingly, Victor Hugo, whose 1831 Notre-Dame de Paris (or The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, as it is known in the anglophone world) garnered a lot of attention to the cathedral (and thus its crumbling state).

Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle (Paris, 1854-1868), t. 8 (Q-S), “Restauration,” 14: “Restaurer un édifice, ce n’est pas l’entretenir, le réparer ou le refaire, c’est le rétablir dans un état complet qui peut n’avoir jamais existé à un moment donné.” For an accessible translation of the entry, see Charles Wethered, On Restoration, by E. Viollet-le-Duc, and a notice of his works in connection with the historical monuments of France (London, 1875).

Interview with Alexandra Prado Coelho for Publico.pt, published 4 September 2018.

Auguste Rodin, Les cathédrales de France (Paris: A. Colin, 1914). A full translation of the text, by Elisabeth Chase Geissbuhler published under the title Cathedrals of France, is currently out of print; following the 2019 fire, David Zwirner Books has published a selection of its chapters by Rachel Corbett entitled The Cathedral Is Dying.

The “functional” gargoyles (that help drain rainwater from the rooftops and away from the external walls of the cathedral) are mostly medieval, but those that populate the superior balustrade of the façade are purely decorative and a nineteenth-century insertion. For more, see Michael Camille, The Gargoyles of Notre-Dame: Medievalism and the Monsters of Modernity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).