The queen is dead, long live the queen

When history-writing and history-writer become one story

(CW for loss of pregnancy and death)

I like to tell stories, so allow me to tell you one about a historian and a queen.

It was the summer of 2019, and I was sitting in one of the reading rooms of the French national library trying to put together a conference paper about the coronation of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century French queens. My first attempt started with a commentary on queens who weren’t crowned and, before I realized it, I had typed several pages of notes on the death of one of them. I filed all that under “notes for the future,” pivoted back to my conference paper, and eventually finished it.

Fast-forward a little and it was now the end of that same summer and I have written over sixty pages about these coronations. It was, for lack of a better word, garbage. And—spoiler alert—none of that would ever make it into my dissertation save for a handful of lines repurposed for footnotes (so I guess no work is truly wasted?). In trying to find a way out of that funk and forward into the dissertation that didn’t involve starting that chapter from scratch,1 the suggestion I got was to go through my files and see if there was anything that sparked joy seemed particularly interesting at the moment. I remembered my notes from the summer and how easily that had just happened so…

“I guess I could start writing the last chapter, the one about death and funerals.”

At that point, I was trying to do this thing of kicking off each chapter with a little case study, a short historical anecdote that illustrated some of the themes of the chapter ahead and set the stage for what would be discussed in the following pages. So I decided to revisit those notes and write a little about the death of the queen who, in short, almost never was, Isabelle of Aragon.

Isabelle was born sometime between 1247 and 1248 and certainly died on 28 January 1271, in a south Italy town called Cosenza. She was the eighth child of King Jaime I of Aragon, the first wife of King Philip III of France, and the mother of four surviving sons at the time of her death (including the future Philip IV of France).

Isabelle was never crowned. Her husband, Philip III, was the first king of France to call himself that right after his father’s death and before being crowned.2 On her way to France with him returning from a failed Crusade, Isabelle suffered a horse-riding accident and fell sick due to complications of a before-term childbirth. But even under these circumstances, her testament still opens with:

“We, Isabelle, by the grace of God queen of the French…”

The statue of Isabelle lying on top of the tomb for her bones, in the then-blossoming French royal necropolis of Saint-Denis (on the outskirts of Paris), also shows her in all her royal state, wearing for eternity the crown that she never received on earth.3

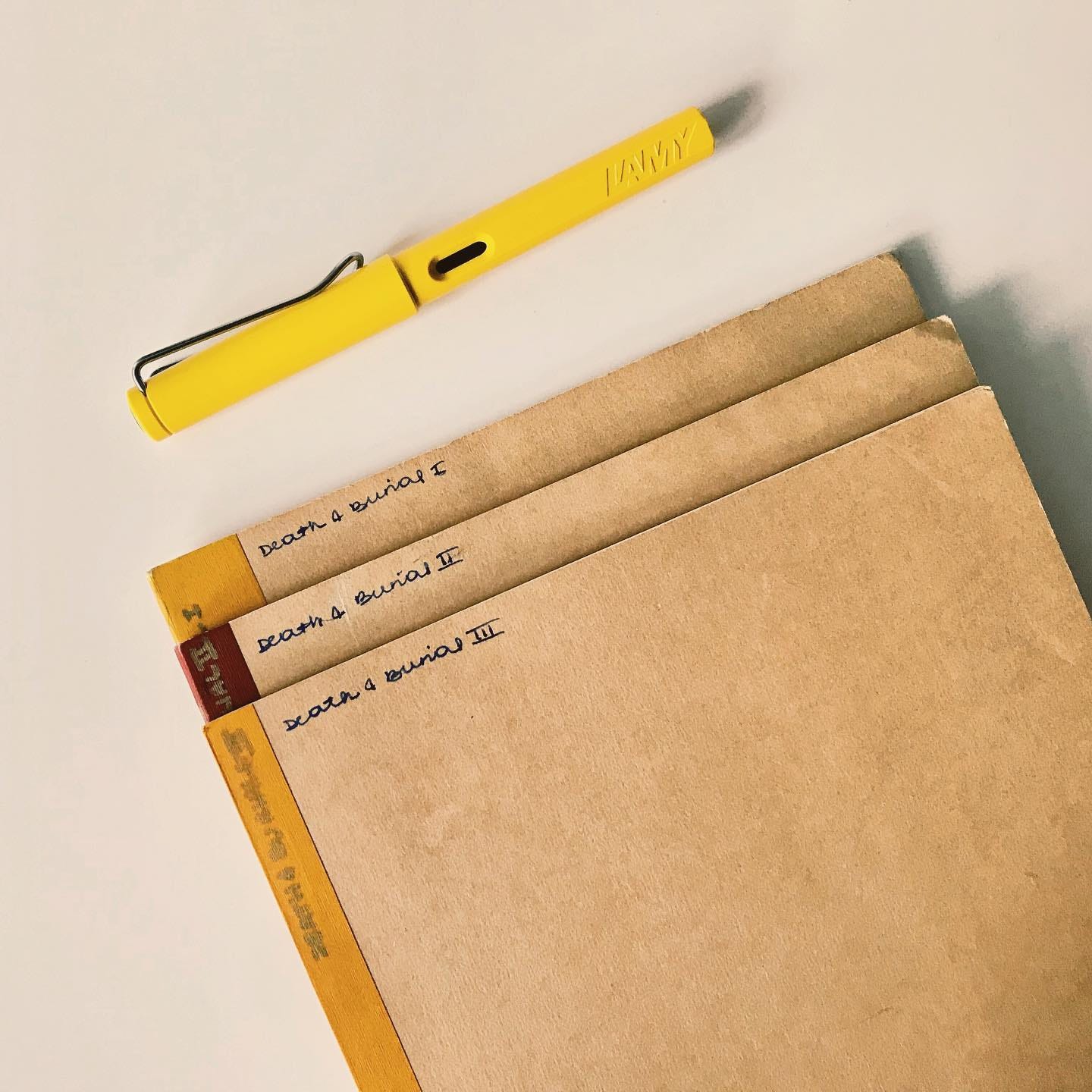

I spent two or three months with nothing but the little we know of Isabelle’s life and the much more we know about her death and burial in Cosenza and in Saint-Denis. Most of this time was spent with Latin chronicles, trying to make sure that what I was reading was correct and how to best translate it to English.

Medieval chronicles, especially those written in Latin, are not exactly welcoming to modern readers. They are long texts, sometimes spanning several decades if not generations, the writing is often dry but convoluted, the authors were usually interested in the most political and divine of matters, and their view on women was not generally great. And I was dealing with all of this, with the added dash that one of the chroniclers I was reading intently and intensively decided that he would very much like to add a lot of details about how Isabelle of Aragon fell from her horse, gave birth to a stillborn, and died a terribly painful death—all wrapped in anti-French political inclinations, of course.

What was supposed to be a short introduction to one chapter snowballed into 30 pages or so. I was excited about this like I hadn’t been in a while (certainly a lot more than I had been about the coronation chapter that started it all), my head was spinning after this intense dive into this one thirteenth-century incident and its political and artistic ramifications and…

…and I was done. I was spent. It was a grueling process, in part because I wasn’t comfortable as a translator and in part (perhaps in no small part) due to how terrible some of these texts were when it came to describing an accident that led a pregnant woman to lose both her child and her life. I had what I can only describe as a burnout episode—and it would take a lot of time (and no small amount of tears) to find my way out of it.

I began writing that chapter in earnest in September 2019. It would change from the introduction to the last chapter of my dissertation to its opening chapter. In September 2022, I presented a very summarized version of it at the first (and only) conference I participated in as a doctor.

And now, it’s September 2023 and I’m thinking about Isabelle’s story again and about how it came to be so entangled with my own story in a way that I had not anticipated. I’m not sure if I’ll ever revisit her story in full, but I wanted to share at least some of it.

I guess sharing stories remains the way we maintain them. And it gives the storyteller some purpose too.

I would eventually get very adept at doing just that: creating a blank document and figuring it out from there. I still hate a blank page on some level but I’ve come to appreciate the opportunity to start with just enough baggage (my previous draft).

The whole “the King is dead, long live the King” thing comes in quite late in medieval history. German medievalist Ernst Kantorowicz found Philip III’s ascension to the throne and to the title of king a very important moment in the history of the monarchy, which he discusses in his 1957 The King’s Two Bodies (a book I do not recommend to anyone unless they’re really into the institutional and intellectual history of that period).

This type of funerary statue, called gisant or recumbent effigy (showing the person buried in a prone position, usually displaying signs of their rank and status in life), often in a white stone like marble, alabaster, or limestone, was a hit in the second half of the thirteenth century and would continue to populate burial sites in France (and England) in the coming centuries.

Loved this! :)