This past week, I mentioned to friends that I missed the Bird App, because where else could I simply post “I don’t have a pet, but I do have a Roomba that constantly makes me go ‘not there!’” and have it make sense in and of itself?

I was a Bird-App user for several years. My first profile there (now defunct) dates back to October 2008, before apps were even the way to experience most of internet. In my mind and heart, the bird app remains a website, one that shows a flock of tiny birds trying to fly a whale whenever it crashes (and it was often).

The Bird App was perfect for blurting out whatever I felt like at the moment, without any elaboration (120 characters!) or an aesthetically pleasing photo. For the former, I had Livejournal; for the latter, Fotolog; for combining both, Tumblr. If I wanted to simply make or contact friends, there was Orkut,1 then Facebook.

Even before the Bird App went through some drastic changes, I had drifted further and further away from it because it had been a sort of lifeline during the brunt of the pandemic and the worst of my dissertation-writing period. I made wonderful friends there, people who remain in my life to this day, but the app, the website, the environment, became intrinsically with and indissociable from those neverending months.

Still, I miss being able to hop in, share a silly thought, and hop out.

I’ve been thinking about this because I would no doubt go there and complain about having to babysit my Roomba.

Plenty of people have used (and continue to use) short-form social media (and various other social media platforms) to be politically and socially active, and I certainly get a lot of my non-standard, non-mainstream news through similar means.

But to me, it was an escape valve.

And also a place to share some inane hot takes that caught me off guard during my day-long stints in front of the computer.

For instance, everyone has been talking about bookshelf wealth, the fact that curating the look and feel of your bookshelves is now a “trend,” and how dare people want to make their book collections look a certain way or another.2

I had an urge to share something about it. I couldn’t quite figure out where.

I ended up writing a note to Substack, which I copy here in full because I think it’s illustrative of this whole thing:

Resharing this post because “bookshelf wealth” keeps popping up for me on instagram and newsfeed.

My hot take is that some people* got really annoyed at the whole “bookshelf wealth” thing because it reminds them that books are—like anything else that can be collected—artifacts, that can be gathered for functionality or aesthetic pleasure.

That, at the end of the day, anyone who buys and keeps physical copies of books does so because they like having, displaying, and looking at them.

*(of course, there are socioeconomic issues that underlie the whole thing—as always, especially when it comes to (interior) design, I’m not denying them.)

I don’t want to elaborate on the subject. People more skilled with words and more attuned to both the book industry and interior design have probably already said more than enough about it.

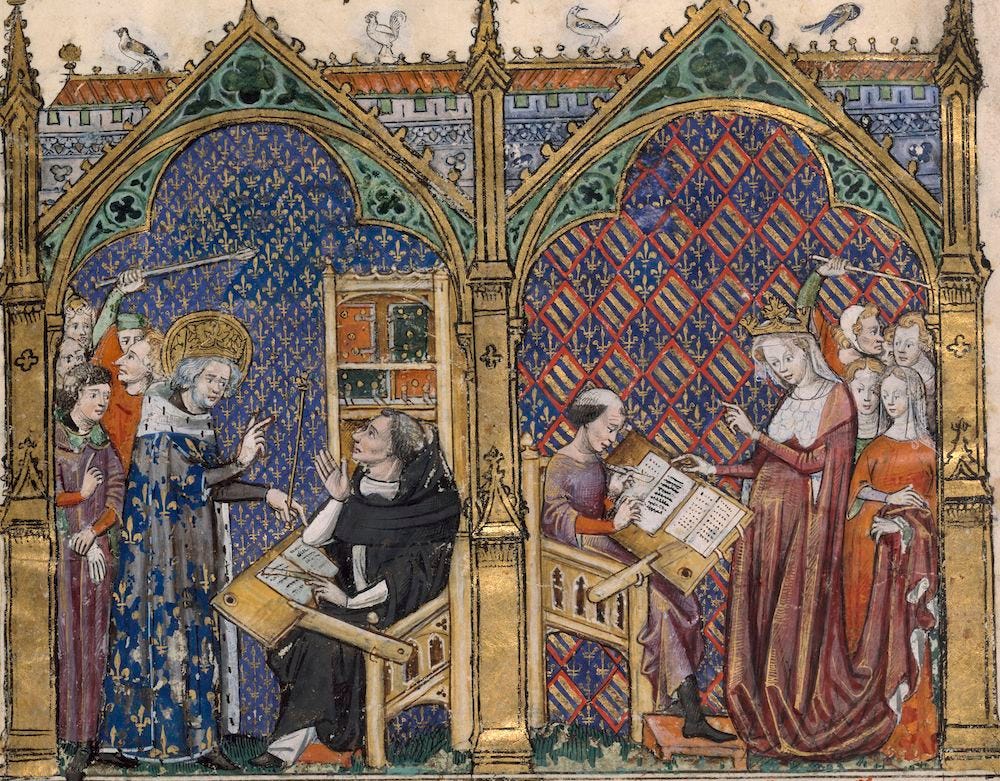

I could add that the creation and care for personal book collections were of huge social and cultural importance in the last centuries of the Middle Ages and onward—and that is not limited to those collections of dozens and hundreds of volumes assembled by the nobility and the royalty. It also applies to prayer book-and-Bible pairs, to little commonplace and recipe volumes, the works. Manuscript, then printed, books would be collected in life and carefully gifted before or in death, featuring sometimes prominently in testaments from various social groups. Even the most humble book could be taken care of throughout generations, gathering marks of use, annotations, and personal mementos.

Not unlike people in different places at different times, we like collecting books and displaying them because they are their contents, sure. But they are also the stuff we are made of, things that reflect our interests, our dreams, our friends and family, our projects, and our tastes.

And sure, you can have a personal collection without caring for what it looks like aesthetically, and you may find that buying an expansive candle or an Etsy vintage-looking print to add to your shelves is not where it’s at. But that doesn’t negate the fact that those haphazard piles of books are meaningless as they stand.

They actually mean something just because they are. And this feeling is not new.

But in a world where space is scarce, resources even more so, and so much of our entertainment has moved to digital formats—and often on a streaming, rather than ownership, model—purchasing physical copies of books and making room for them in our lives is in itself a form of wealth.

In the late 1520s, Baldassare Castiglione wrote a dialogue/philosophical treatise commonly known in English as The Book of the Courtier. Much like the Platonic dialogues, Castiglione’s puts historical characters together in the scene to discuss possible answers to a question—here, what makes a good courtier? Each person-character then expounds their proposed qualities, such as being a good dancer, a good speaker, and being knowledgeable in the arts (both visual and textual).

Early on, Lodovico Canossa proposes a characteristic of the good courtier, one that would go on to have a life of its own beyond (perhaps even greater) than Castilione’s Book:

“I have discovered a universal rule which seems to apply more than any other in all human actions or words: namely, to steer away from affectation at all costs, as if it were a rough and dangerous reef, and (to use perhaps a novel word for it) to practice in all things a certain nonchalance which conceals all artistry and makes whatever one says or does seem uncontrived and effortless.”3

The “novel word” translated here as “nonchalance” is the much more alluring sprezzatura in the original. Sprezzatura is thus the backbone of any good courtier-ness. It should be the orienting principle of any and all performance in public, making it seem like any calculation and all the hard work to master knowledge and one’s manners were a natural inclination or virtue. To dance just the right way. To speak with just the right tone. To appreciate just the right art. To dispute in just the right measure.

We live in a world drenched in sprezzatura even when we don’t acknowledge it. It is not just the cheerful Sugar Plum Fairy or the perfectly in-sync corps de ballet in Swan Lake. The perfectly crafted friendly work email that takes up hours. The search for the perfect messy bun. The perfect no-make up look. The effortless French Tuck.

It’s in our everyday lives—our daily performances of our selves, as sociologist Erving Goffman would put it. According to him, the objects that surround us in our everyday lives are like props, that we use differently to affect different audiences.4 Which means that our exercises of sprezzatura may not limited to our bodily selves and can also concern those very props. The objects we surround ourselves with. The stuff that constitutes who we want to seem like, for others and for ourselves.

It can, in fact, touch many a bookshelf.

A carefully curated and put-together collection, meant to look the opposite of calculated.

Perhaps then the rage against the new “trend” is two-fold. It irritates many because it blurs the line between reader and bibliophile (in its purest sense of someone who likes books). But it also annoys those who have embraced this blurred line because it’s a constant, flashing reminder that there’s nothing casual about how curated those shelves are, no matter what we like to say to ourselves.

In other words: everybody wants Kathleen Kelly’s bookshelves, but no one wants to admit a lot of work goes into making it a reality.

But this is all too much (and it could continue going and going).

Sometimes, a tweet was just a tweet.

I don’t have a pet, but I do have a Roomba that constantly makes me go "not there!"

quickly followed by

bookshelf wealth annoys bc everyone wants Kathleen Kelly’s bookshelves but not to admit the work that goes into it

Carefully crafted and curated and casually living side by side.

Online, much like offline.

January round-up:

The Parisian, by Isabella Hammad

The Weight of Things, by Marianne Fritz (trans. from German by Nathan Adam West)

White on White, by Ayşegül Savaş

In the Eye of the Wild, by Nastassja Martin (trans. from French by Sophie R. Lewis)

The Singularity, by Balsam Karam (trans. from Swedish by Saskia Vogel)

This Little Art, by Kate Briggs

A Invenção de Morel [The Invention of Morel], by Adolfo Bioy Casares (trans. from Spanish to Brazilian Portuguese by Sérgio Molina

The Emissary, by Yoko Tawada (trans. from Japanese by Margaret Mitsutani)

MySpace wasn’t really much of a thing in Brazil. Orkut, on the other hand, became a quintessential Brazilian social media to the point where its twentieth anniversary was celebrated across humor pages on Instagram. My favorite post is this one.

If you’ve been around long enough, you’ve seen the previous iterations of this: “how dare people organize their bookshelves by color?” or “why are all of the spines in these books hidden?”

Baldassar Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, cite from trans. George Bull (Penguin Classics, 2003), p. 67.

Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1959).

I love how you introduce me to new words and concepts; "sprezzatura"! Also, I had not even heard of "bookshop wealth"...possibly bc I don't have Instagram...but I confess to ogling over images of curated bookshelves 😀 I think you make such a good point here though, about our things being connected to who we are. When I pick up a book from my bookshelves, it often brings up memories of when I first encountered it; I often find postcards or bookmarks I have stored inside it. I love making those connections 💕