"I was here. This is my story."

Notes on memoir-reading as a non-theorist recently arrived to memoirs

If you missed my last missive, allow me to catch you up: I have recently brought to Juliana, cronista a series of extremely short book reviews that I call read/don’t read (a huge thank you to everyone who came on board!). As some might have noticed, in the last couple of months I have read (via audiobooks) several memoirs—more than I had in all previous years combined. The reason is pretty simple, in my mind at least: I have been doing a lot of crafting that leads to a lot of time where my thoughts can either just drift into nothingness (or a never-ending list of mindless YouTube videos) or I can put my ears to good use and listen to a good story or two. I’m not the best at auditory retention, so novels (which I prefer to savor at my own pace anyway) were out and memoirs felt like the perfect sweet spot of being told a story without having too many characters involved at any one point.

What you have not noticed, because you couldn’t have, is that drafting every list that makes its way to read/don’t read posts, I go into GoodReads and Storygraph and see what people have been talking about any given book, to see if I had missed anything glaring or if my thoughts find some time of resonance with the crowd there. My favorite thing is to take a look at the 2-star reviews, because they tend to be a little more informational than the 1-star reviews and so they give me a little more food for thought.

Or they do, sometimes, but with memoirs, things get a little tricky.

Over and over again, I come across a similar type of criticism. Some of the comments go longer, others are more succinct, but they all boil down to the same feeling: Memoir authors are too self-centered, too self-absorbed, too preoccupied with their own stories and feelings and…memories.

I found it funny the first couple of times. After that, my historian brain started to kick in, because funny coincidences tend to lead into more interesting questions when they become recurring enough. And the charge against self-centered memoir writers is recurrent enough that merely remarking on it was not enough. What does it mean to call a writer self-absorbed, especially one whose work consists of personal experiences, ethics, and relationships? What does it mean to pick up any type of autobiographical piece of writing and come out on the other side with the single (or main) conclusion being that the author was too self-centered?

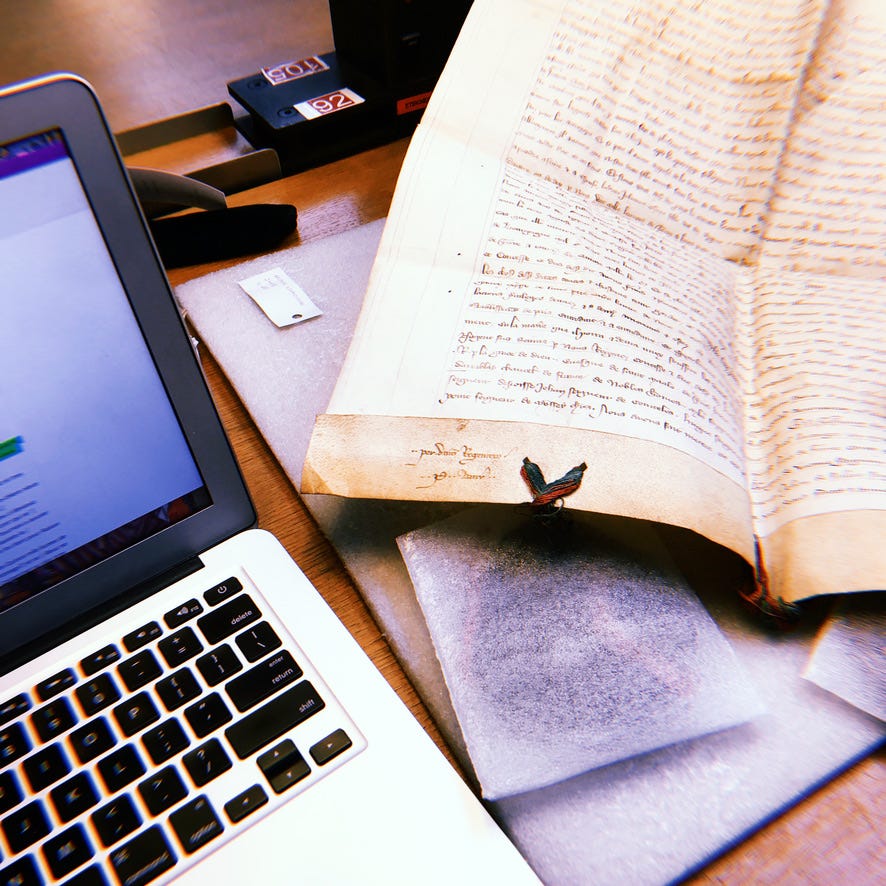

In a different lifetime, I worked on medieval testamentary documents as a form of autobiographical writing. That is not to say that traditional life-writing did not happen in the Middle Ages—just that the people I happened to be studying happened not to do any of it. And so I decided to approach those end-of-life writings as testimonies of what each person wanted to highlight of themselves, who and what they valued most, their prized possessions and the lands they felt most attached to (the former of which led me to spend more hours than I care to compute figuring out medieval spellings of French townships that no longer exist and trying to place them on maps), a way to say “I was here. This is my story.” It was, weirdly enough, a fun way to wrap up my project (it was the last chapter I wrote for the dissertation), after spending so many months reading and re-reading those documents and trying to make sense of them.

As a material culture and body history enthusiast, I took some liberties with the interpretation of the material, relying on a not negligible amount of anthropology (Alfred Gell and Annette B. Weiner both feature in an explanatory footnote somewhere). But navigating a traditional corpus (documentary evidence of wills and testaments) through a less-than-traditional route (what if we read them as autobiographical and not just formulaic?) also allowed me to read some theory on modern life-writing and use it as a framework to see how people have written about themselves across time and space. It’s a world in and of itself, one that I only managed to take a peek at.

Indeed, autobiographical writing is as old as time. I mean, the first text we currently have to be attributed to a single, named author is a type of religious poem that both praises the deity it addresses and lists the wrongs done to its author and why they should be redressed by divine intervention. That it was written by a woman, called Enheduana, in honor of a goddess, called Innana, only adds a little something extra to it.1

That is, of course, a type of self-writing of a very different variety from most memoirs published today, but the thousands-of-years-old history behind autobiographical writing reminds us that writers of various kinds have always liked a little bit of navel-gazing. And, without it, we wouldn’t have works like Augustine’s Confessions, Montaigne’s Essays, or Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, three as-disparate-as-they-come types of personal narratives that in one way or another drink from the same source: proclaiming “I have gone through this transformative, enlightening, unique experience. I have tried to break away from the common of my peers and engage with others from a different standpoint. There’s something specific about where I stand in the world. I need to share this with someone.”

Although born as a type of political remembrance, through which figures (namely men) could reflect and recollect their years in the public sphere, the modern memoirs that fill bookstore shelves seem to have taken a turn towards the meditative, the contemplative, the sentimental, and the personal (none of which I use derisively). In the 1990s, the writer and literary critic William Zinsser noted (perhaps more than a little derisively) that “until this decade memoir writers tended to stop short of harsh reality, cloaking with modesty their most private and shameful memories. Today no remembered episode is too sordid, no family too dysfunctional, to be trotted out for the wonderment of the masses in books and magazines and on talk shows.”2

And such a turn towards unflinching openness requires, if taken earnestly, something like a commitment, or maybe a compromise, from both author and reader, to inhabit an unstable middle ground. On the one hand, the reader requires that the author be truthful and honest, ideally to a painfully earnest degree, in such a way as to offer as seemingly an unmediated experience as possible, so that the reader can feel like being in the author’s shoes. On the other hand, memoirs require a high degree of craftsmanship, because the narrative thread—the emplotment of one’s experiences and life3—is not given merely by the chronology of events (a memoir, just like memories, may not even follow a strictly progressive chronology). The logic of emotion and the coherence of self-knowledge and experience are not linear, straightforward paths, and if the writer feels the connections between A and 3, they are not a given and need to be delineated (even if in the most impressionistic of manners) so the reader can follow along that precise development. But if the narrative construction is too loud, too clear, too logical, it risks undoing the emotional and psychological effect it seeks to create.

This is nothing new: in the 1970s, the critic Philippe Lejeune had already articulated the autobiographical pact as something that aligns author and reader in the event of the text, affirming on the one hand the univocity of author and narrator and on the other the understanding of the reader that such unified “I” informs her reading of the text as truthful, if not objectively true.4 And there is no autobiography/memoir without an audience, because self-writing is an exercise in the making of a narratively cohesive identity through the literary performance of such cohesion.

I’ve written before about sprezzatura, a notion presented in the sixteenth century by the Italian author Baldassare Castiglione to mean a sort of carefully crafted carelessness in the court (and I’m obsessed enough with the idea that I keep coming back to it). No one can know how hard you tried to achieve perfection, no one can see the machinations going behind your eyes when you walk, when you talk, when you dance—or when you write about these things as an awkward teenager, an ambitious college student, an underpaid salary person. As a casual reader and now even more casual thinker of memoirs, I wonder if this is the genre where Cicero’s neglegentia diligens (“diligent negligence”) is tried at its very limit.

The modern, sentimental (again, not pejorative) memoir requires a starting point that is not always acknowledged but informs this complicated exercise in ease: to some degree, the emplotment thread is one of self-mythologizing. This is an activity we all engage with, for better or worse, to a greater or smaller degree, consciously or unconsciously. We are always already construing stories that justify our actions, trying to find rational and causal connections between events in our lifetime, in the lives we share with others, in our intimate emotional world and our external façade. How many times have the words “In hindsight” or “Looking back now” introduced an explanation to myself more than to whoever was listening to me?

To open a memoir and jump into it is, in some ways, an acceptance of someone else’s self-mythologizing. A not-so-tacit joining in their exploration of their own emplotment. The charge against “self-centered” and “self-absorbed” authors could come from the tricky balance of neglegentia diligens not being achieved in a proper manner, with too much focus on the sentimentality or on the construction of emplotment. After all, the intended effects of writing are always subject to how those constructions will be received, processed, and felt by the reader, and so there’s always room for disagreement, some noise in the transaction. It is up to the writer to establish the terms of her work, up to the reader to accept them or not.

But I think there’s something deeper, and more pernicious, there than a matter of mismatched intention and reception. Or rather, the factor I have in mind causes such mismatch even before the book is opened and the first page flipped: It seems to me some readers are approaching memoirs (and literary writing in general) with a utilitarian perspective, and I think this needs to be considered in its broader causes and consequences.

The self-help market is, and has been for some time now, a real industry inside the book industry, covering ever more areas of our lives: spiritual, business and financial, professional at large and in its different fields, culinary and dietary, well-being in general. It may not be my cup of tea, but it seems to be a lot of people’s, which is fine and good on its own, but here’s my problem with it: self-help is, and always will be, utilitarian. There’s no reason to purchase and consume a title under this umbrella if not for its practical, actionable, and useful advice, regardless of the literary quality of the form.

And that is all fine and good. Personal preferences aside, if there are readers, there are writers, and the numbers made each year are undeniable, even coveted by other niches. It’s all fine and good—until this utilitarian perspective of the written word turns towards other genres. Or, to put it differently, when the same logic is then deployed towards other forms of writing. Literary forms of writing. Like memoirs.

The self-help memoir is not a newly invented hybrid, and I can guarantee that if you go to your local bookshop and take a look at their autobiography/memoir shelves you will find more than a handful of titles that fall within this category: books whose content is not just tales of overcoming obstacles, but also of how you too can overcome the obstacles in your life if only you will change your mindset, change your perspective, try a little harder, try this method of organizing your life, or that method of organizing your shirts. And as if by osmosis, those other memoirs, the ones that simply tell a story and ask the reader to be a friendly and understanding ear, now lack something. They lack actionable advice, a pat on the reader’s back. They are too self-centered. Too self-absorbed. They are not useful.

I’m not sure where to go from here, in more ways than one. I have been sitting on this draft for several weeks now, feeling that something is missing for it to be a complete and coherent personal essay. It was only a couple of mornings ago, as I was brewing coffee, that I realized that in a way I was falling victim to the very problem I pointed out: a search for a concrete, if not actionable, so what, an instrumentalization of what started off, and can in fact remain, just some notes, a handful of observations and subsequent thoughts, hoping to find an agreeable ear or two, without the need for a conclusion or lesson (be it grand or small).

If you want to read some of my thoughts on the growing utilitarian perspective of the humanities (and, by extension, of the arts) in my piece “Like the ogre in the fairy tale…: A defense on how life and the humanities feed each other and feed our selves”—so I won’t repeat myself (I do want to add its full title and subtitle because 1) I quite like them; 2) I think they will hopefully hook you in enough to get you to click on the link).

For now, I will finish this by doing what some of the best memoirs do: circling back to the beginning of my story with this topic. In medieval testaments, persons or institutions named as executors of the documents’ clauses were transformed into a type of legal extension of the testament writer, charged with the adequate distribution of goods and gold. But I also consider them a sort of social extension of the writer, as their task was intrinsically connected to keeping someone’s memory alive and cared for.

In a way, isn’t that what we too become when we hear the calling “There’s something specific about where I stand in the world. I need to share this with someone” and accept it?

You can read Enheduana’s writings (with a very informative introduction), in the recently published Enheduana: The Complete Poems of the World's First Author, trans. Sophus Helle.

William Zinsser, Introduction, Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998).

The historian Hayden White defined emplotment as “the way by which a sequence of events fashioned into a story is gradually revealed to be a story of a particular kind,” in his Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973).

Autobiographical fiction—which explicitly uses invention—is a robust genre, but faking truthfulness is a full breach of contract.

Wow. So fascinating. I do not unfortunately have a humanities degree (I thought I could save the world with an environmental degree) but I am slowly developing an interest in medieval history and your dissertation sounds so interesting. I love reading memoirs (it feels like an acceptable way to be nosy and I just find people interesting). I had read about Mergery Kempe recently in Femina and would love to read her. And I have been eyeing out Enheduana and it is on my wishlist. This is further encouragement to pick it up sometimes sooner than later.

Love a historian and somebody who has to think about memory delving into memoirs! I studied private diary writing by women and had to think so carefully about purpose, audience, why or why not things were recorded, etc and it’s absolutely made memoirs and similar books so interesting to read because they’re the opposite - the person has a given audience in mind and is performing and remembering publicly. I love the rhythm and style of your writing so much, please share your crafting adventures with us sometime!