Like the ogre in the fairy tale…

A defense on how life and the humanities feed each other and feed our selves

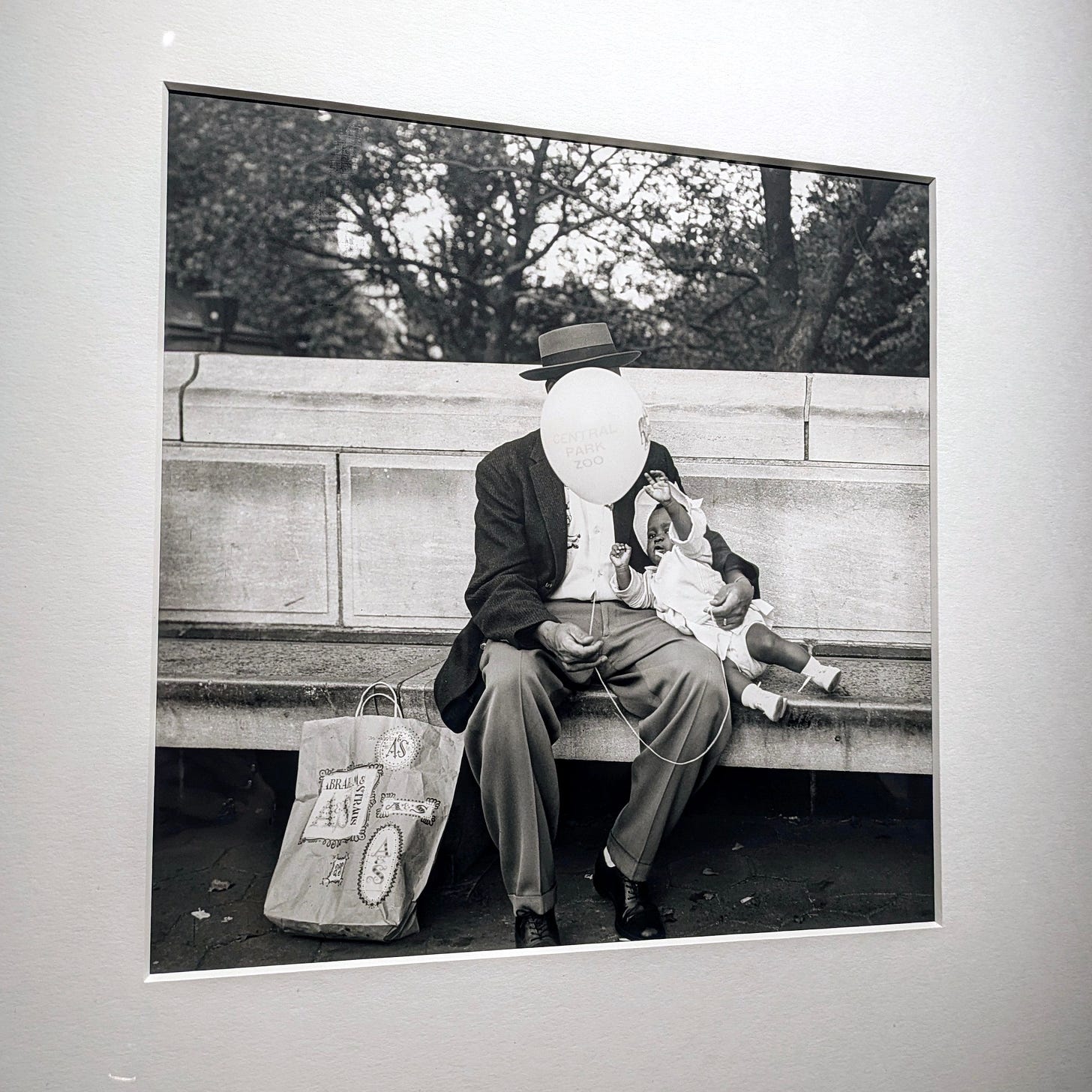

Recently, I had the chance to visit an exhibition of photographer Vivian Maier before its closing in the New York Fotografiska (which also closed on the last weekend of September). Maier was a nanny/governess throughout most of her life, but what is of interest is that she also spent decades photographing herself, others, and the little details of life around her without ever sharing her photos, the negatives for which were found in a warehouse years after her death. Poignantly, one of the wall texts begins with a short excerpt from Georges Pérec about the ordinary things of life:

“[But] how should we take account of, question, describe what happens every day and recurs every day: the banal, the quotidian, the obvious, the common, the ordinary, the infra-ordinary, the background noise, the habitual?”

In the exhibition, the quote introduced the explanation for a section titled “Theater of the Ordinary,” highlighting Maier’s keen eye to, in the words of Anne Morin, “where the ordinary sheds its skin and becomes extraordinary.” Indeed, the selection of photographs of the entire show demonstrates an attention not only to details of everyday life but to its margins. In the 1970 parade to welcome the Apollo 13 astronauts, her gaze and lens are turned to the audience, the children running around, the families, a group of men leaning against a wall and smoking a cigarette.

But Pérec’s original question goes beyond that. It comes from a 1973 text that questions what even constitutes “the extraordinary” and why the world pays more attention to it than to the nitty-gritty of life. “What speaks to us, seemingly, is always the big event, the untoward, the extra-ordinary: the front-page splash, the banner headlines,” he states in the first line of “Approaches to What?”1 It is a provocation, a call to arms for every person to break away from conformity to the habitual, “that which seems to have ceased forever to astonish us.” For Pérec, you do not need a camera and a particular type of aesthetic sensibility for this exercise: The “trivial and futile” are ultimately what makes the essential, and the truthful, of life.

My literary friends would see in the list of questions raised by Pérec an extensive exercise in close reading of the material world around us. In “Approaches,” he refers to “our own anthropology, one that will speak about us, will look in ourselves for what for so long we’ve been pillaging from others,” making me think of thick descriptions employed by Clifford Geertz and other ethnographers. Ultimately, it is the same practice: to look attentively, to look closely, to see and not just look at the end of the day, to try and make sense of what is seen in relation to each other. To sniff and follow the scent of people across streams and bushes, like a hungry ogre in a fairy tale.

When I set out to write this week, neither Pérec nor Maier had been on my notes. Yet the mind has its own ways of making sense of our intentions, and I ultimately think that what came before and what comes next is not dissociated. Because my original intention for this week was to write about a small book about the historian’s craft, what it means to think about the past, and why I still believe the humanities are the only possible way forward. Like an ogre in a fairy tale, let us continue on this trail…

There is one medieval French historian who has always loomed large over me. One of the founders of the Annales journal and its unofficial school with a strong interest in geography and sociology as complimentary to history, Marc Bloch informed many of the readings and influenced a good number of the professors I came to meet over the years.2 Of his large monographs, chapters of his magisterially dense (and yes, at times very boring) Feudal Society were mandatory reading for one of my undergraduate seminars in medieval history, and I came to revisit it in its entirety (or almost) for my qualifying exams for the PhD. The Royal Touch, a study on French and English medieval beliefs in the power of kings to heal scrofula by touching the sick, was a mandatory reference for my honors thesis on Saint Louis IX of France.

But it wasn’t from one of these books, nor any one of his articles, that I picked the epigraph for my dissertation. Neither of those books has had as lasting of an impact on me as one of their much shorter siblings. Today I sit with a paperback copy of it, as I have sat with its Brazilian counterpart in my heart since my undergraduate studies. Having had the chance to revisit it now, a little more mature, a little more well-read, and a lot more open to feeling it and not just thinking it, I can reaffirm the status in my personal canon of Marc Bloch’s The Historian’s Craft.

Its French title is, I believe, a lot more meaningful, and not just because it comes across as more forceful: L’Apologie pour l’histoire is, like the title suggests, not just about what the historian does and how, but a true defense of history as a meaningful field of inquiry. The first line of the introduction couldn’t set this up more clearly, reporting a simple question asked to him by a young boy years before: “So, Daddy, explain to me what is history for.”3

The problem touches on the legitimacy of history as a field and has made much ink run in attempts to address it. In this sense, Bloch’s text is not without peers. There’s an old tradition of historians not taking their work for granted, justifying what they do and why it’s important, starting with Herodotus. But what makes The Historian’s Craft unique, what makes this short quasi-manual stand out, is that it is more than a testament to a discipline. Marc Bloch, a Jewish veteran of World War I, wrote this defense of his craft and the importance of what it brought to the world as a member of the Resistance in World War II. The drafted pages never got a final revision by the author, nor did the draft ever find its ending: his remarks were left unfinished when, captured by the Gestapo, he was assassinated on 16 June 1944 as the German army fled Lyon after the Allies invaded Normandy. His eldest son, Étienne, would later revise the first edition organized by his father’s friend Fernand Braudel, reinserting pages and editing choices that had been missing from that earlier publication. Unfortunately, the translation currently available to English readers relies on the slightly shorter version of the text and offers some linguistic choices I am not a big fan of.4 Still, the fact that it has been often reprinted and republished since its first coming out in 1953 stands as a witness to its strength.

Bloch never sheds his skin of a medievalist, and references to this period abound. However, he fully assumes the role of a man of his present, using examples from Western European history at large, referencing archaeological digs, advocating for the importance and the imports of developments in the social sciences, and recurrently mentioning historical moments that touched him personally, like the Dreyfus affair (the context for Zola’s famous J’accuse letter) and the first world war. It doesn’t mean he assumes the position of a reporter: only sparingly does he explicitly address the lived conditions of the 1940s. Likewise, his own role in World War II remains understandably vague. Even in the Introduction, when he explains why his citations will be made from memory, the reasons are left for the reader to uncover: “The circumstances of my present life, my current impossibility of reaching any large library, the loss of my own books, make it so that I have to rely much on my notes and on my knowledge. … Will I one day be able to fill out these gaps? Never entirely, I fear.”5 Medievalist though he may be, Bloch found it impossible to ignore the conditions created by the recent past and present and how they affect his possibilities of engaging with history.

Because of Bloch’s timeliness, The Historian’s Craft feels larger than its intended form of a manual. It also reads like a manifesto, an explicitly political one at that.6 Marc Bloch believed that, despite the need for a robust education that should include much respect for the contributions of the social sciences to history writing, the historian should be first and foremost a person of their time.7 In fact, in The Historian’s Craft, he defines history as the science of humans in time.8 That means both the past time and the present; erudition about the past can only be of real value if paired with a critical, but real, experience of the living present. And real experience is, needs to be, intrinsically connected to action. “In our day and age, more than ever exposed to the toxins of lies and bogus rumors, what a scandal for the critical method not to be present, not even in the tiniest of corners of the curriculum. For it is no longer just the humble auxiliary in some workshop activities. Now it sees open before itself far wider horizons; and history has the right to count among its most reliable glories to have thus open, by elaborating its technique, a new route for men towards the truth and, therefore, to justice.”9

You could say it is a naïve assumption, and perhaps it is. History, some would say (including some of Bloch’s contemporaries) is nothing but propaganda, textual play, or antiquarianism at best. But some books have a way of touching you in more ways than one, to make you feel that plus ça change, yet here you are. Or rather, here I am, still being touched by it, despite all the bruises, because… Because it still resonates. Because I still hang on to the notion that, without this, what is the point?10 If not for the people, the human matter that animates life here and now and there and then, what are we left with?

There is one passage, two short sentences in the middle of the chapter dedicated to “History, Men, and Time,” that has lived in my head since I first read it, some fifteen years now. I have read and re-read so many times since, and it has such a special place in my heart that I knew, when I finished the final text of the dissertation, that it had to be my epigraph. In defending the true historian against the mere erudite, Bloch says: “The good historian resembles the ogre of the fairy tale. Where he senses human flesh, he knows there is his prey.”11

Bloch was writing against a type of history that focused on macro political and economic structures, big-picture events, and ignored the most basic constitutive element of history: the people who make up each and every society. He was also against the type of romantic biography that celebrates their main character as a triumphant hero. Society, and what individuals made of it—the human flesh that animated it—was at the center of his interest. I cited his study about the royal touch: Bloch was not so much interested in the royal aspect of it, but in what made the people believe in its power. The ideas, the sentiments, and the practices that gave life and continuously supported this miraculous healing.

This interest in the flesh that builds what we call society is what Maier saw and made us see, it’s what Pérec wanted his readers to pay attention to, it’s what Geertz encouraged his students to see. It’s what drives the best thinkers, the best academics, the best authors, the best artists. It’s what scares so many into viciously combating the humanities, the social sciences, the arts: if there’s no human, no humanity, only phantoms and ideals, then what is said, goes. There’s no need for an encounter of minds across time and space.

Because my head sometimes spins at a hundred miles an hour with whatever direction it picks, it went after another book I have recently revisited after first encountering it during my undergraduate studies. I spent most of the spring of last year doing research on twentieth-century North American and European collectors of Persian and Arabic manuscripts for a project I had been called to contribute to, and the recurring concept looming large over my head but never fully addressed (for lack of time and space in the piece I was writing) was the aesthetic of the exoticized “Oriental” Other. So, coming back from my summer trip last year, I felt like it was time to go back to Edward W. Said’s Orientalism.

I may come back to Orientalism more at length in the future, but for now I want to touch on two notes from Said’s preface to the twenty-fifth-anniversary edition rang throughout my re-reading of The Historian’s Craft last month. The first concerns the manifesto aspect of Bloch’s short book. Much like him, Said also posits that knowledge—of the kind resulting from “understanding, compassion, careful study and analysis for their own sakes”—has the potential to affect the real world in concrete ways.12 It is an understanding of the usefulness of historical, sociological, and literary studies that goes beyond what seems to be a growing instrumentalization of these fields in contemporary discourse: “History is useful because it gives us answers about X.” As an avowed classically trained literary historian, Said was not afraid to mobilize the awkward, almost old-fashioned notion of humanism as the center for his intellectual-political project, “to be able to use one’s mind historically and rationally for the purposes of reflective understanding and genuine disclosure.”13 Both authors seem to agree that the usefulness of critical historical thinking is not about the answers but about the questions, about understanding rather than judging, about the process and not any strict and settled result.

The second point came a little less polished, a little less emotional, but just as present. My copy of The Historian’s Craft came to me pre-owned. I don’t know how many different hands flipped through its pages, now even more battered than they were. But at least one person read the text with some attention and left marks in black ink throughout its pages, mainly marginal lines highlighting certain lines and passages. Despite this, there are no written notes, except for one word: “translation.” It is placed in the middle of a discussion about how language and vocabulary need to factor in the historian’s consideration of the craft as, unlike the hard sciences, internationally standardized formulas, symbols, and numbers are not at hand.14 The paragraph marked by that note ends with the following lines: “…as soon as appear institutions, beliefs, customs, which make up in a profound way the very life of a society, the transposition into another language, made in the image of a different society, becomes a project full of dangers. For to choose an equivalent is to postulate a resemblance.”15

Despite it not being my own professional craft, the challenges of translation have always been of interest to me—personally, as I have discussed in previous posts, but also professionally. I am not a great Latinist but it was sitting with Latin sources for hours on end—trying to make sense of what they meant and how they meant it, to then in turn try and express my ideas about them in a language that is not my mother tongue—that some of the most rewarding a-ha! moments came. It felt like solitary work at the time. But I now remember how many times I was able to confer with colleagues and make use of an immense amount of work from previous generations of scholars, and it makes me feel a little less alone. Bloch argues elsewhere in his book that the single historian cannot account for everything—good work is done by branching out from disciplinary silos but also by sharing questions and methods with others. Said would say that humanism is “sustained by a sense of community with other interpreters and other societies and periods: strictly speaking, therefore, there is no such thing as an isolated humanist.”16 Looking at that single word on that page, that’s how I felt: a little less isolated.

It is hard to conclude a text like this. Part memoir, part essay, part a strange kind of manifesto—maybe a little closer to The Historian’s Craft than I had originally intended. Perhaps it should be left incomplete. As Bloch states, “the incomplete, even if it tends to be always overcome, has, for any spirit slightly passionate, a seduction that is well worth that of the most perfect completion.”17 Ironically, this would end up being an apt description of the book. So perhaps the only way then to conclude here is to cede a little more space to Bloch once again, to leave with the words that concluded my honors thesis presentation some fourteen years ago, it the ellipsis that closes The Historian’s Craft and calls attention to its state of perpetual, yet immensely valuable, incompletion:18

“To sum up, the causes, in history as elsewhere, are not postulated. They are to be looked for. …”

Georges Pérec, “Approaches to What?,” in Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, trans. John Sturrock (London; New York: Penguin Books, 1997), 209-211.

Just as one example, Jacques Le Goff, in the introduction to the newest French edition of the text (translated in the Brazilian edition I read some fifteen years ago), explicitly calls himself a disciple of Bloch despite never having met him.

Marc Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, trans. Peter Putnam (New York: Vintage Books, 1953), 3. All references, except on note 6, refer to this edition.

For this reason, I am translating freely from the French edition of the text, but I offer references to the standard American edition of the text for those who will be interested in pursuing it.

Bloch, The Historians’ Craft, 6-7.

After I finished this text, when I was collecting the footnotes and references to add them to the appropriate places, I noticed that Peter Burke also calls this a manifesto in his preface to a more recent edition of the same 1953 translation of the text, so I leave a reference to his text as well (which did not inform my reading of Bloch but might be the starting point for you depending on the edition you find): Peter Burke, “Preface,” in Marc Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, trans. Peter Putnam (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992), vii.

I take one important liberty here, that I hope my readers will allow: For Bloch, the historian is always a he. He fought an overreliance on the “spirit of the guild” of historians on several occasions but never questioned that of male historians. Sometimes I like to silently fix that; it’s my way of being acutely aware of the present in my engagement with the past.

Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, 47.

Bloch. The Historian’s Craft, 137.

It is impossible not to think here of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go (2005), which I have also read recently, and the role of arts as proof that we are here, we are human and we matter. I will leave this remark on a footnote, to avoid yet another tangent, or the risk of spoilers for anyone who hasn’t read it yet.

Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, 26.

Edward W. Said, “Preface to the Twenty-Fith Anniversary Edition,” in Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 2003), xix.

Said, “Preface,” xxiii.

Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, 162.

Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, 162.

Said, “Preface,” xxiii.

Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, 18.

Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, 197.

Such a beautifully written reflection, Juliana.